Strangers

America's "stranger culture" changes your personality.

“And the ladies treat me kindly

And furnish me with tape…”

Some years ago, when I was living in Brussels, my old Budapest friend Orsi and I took up the good habit of taking the weekend off, driving over to the Flemish side of the country, and staying at a spa. If you harbor prejudices about some parts of Northern Europe as a bunch of elderly people running around in the snow in a state of nature and then roasting themselves in overheated saunas, these are absolutely warranted. This is exactly what happens in these spas — in fact your clothes are confiscated at the reception lest you make other people in there feel “uncomfortable” by having clothes on you (social democracy). And yes, at the entrance stands a bronze statue of a naked woman on a bicycle. Eat your heart out, Godiva!

After a few timid trips to this establishment, which really did bring our old friendship with Orsi to a new level, I developed a theory I was determined to test empirically: that this spa might be the perfect place for a woman to go to by herself for the purposes of relaxation and reading, because there is no way anyone would come and bother you in that already pretty social-distance demanding situation that is nudism. And I was right. Thus began my short-lived career as nudist-spa patron, where I would read heavy books, write heartfelt essays, not speak to anyone for days, and sleep like a baby. Or I would have, if it hadn’t been for … Americans. And so it came to pass that one day there was an American at the spa, in the middle of nowhere in Flanders, who somehow saw this woman by the steam room, butt-naked and reading The Assyrian Army vol. III — having paid a small fortune and taken multiple trains to get there — and for some mysterious and culturally very inappropriate reason thought to himself, “I’m going to go and talk to her.”

I looked up at this guy over my book, who was so happy to find somebody “reading in English”, and I thought to myself: You gotta be — fucking — kidding me. Can’t a woman these days frolic around in a public space without any clothes on and be left alone?!

These people … They really will talk to anyone.

*

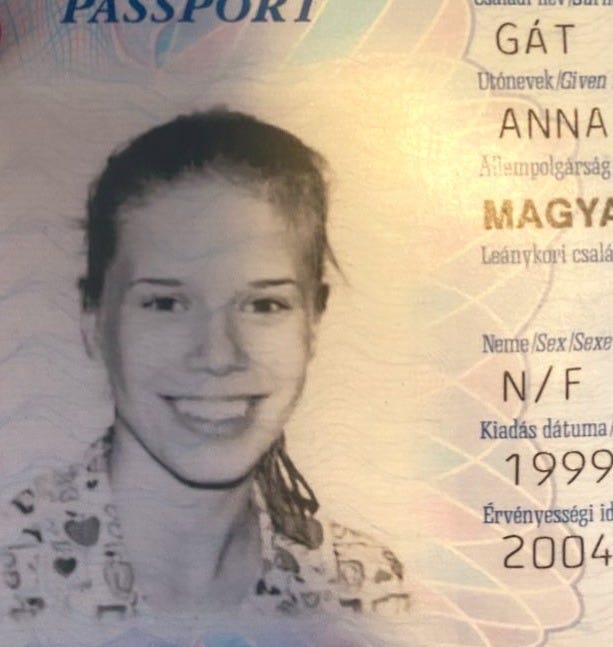

I was going to write this piece right after “Grieving in America”, that little coda to some of last year’s great losses in my life. How America, unlike the many places around Europe that I have lived in, has a stranger culture — as I will argue, for good reasons — and how that is both what’s great and hard about living here.

Then, as usual, my travel schedule shook up my philosophy schedule — why else we travel anyway? — and so this piece now must come after “American Catalysis” where I ended up writing about mentors, friends, and muses; in short, some of the most important people in my life who shake up more than just my travel or philosophy schedule.

In the “Catalysis” piece, I wonder aloud what makes people not strangers. In a world so open, so chaotic, so rootless as America or the internet is, how do some people still find themselves related, often in surprising, hard to describe configurations that become definitive for how their lives turn out.

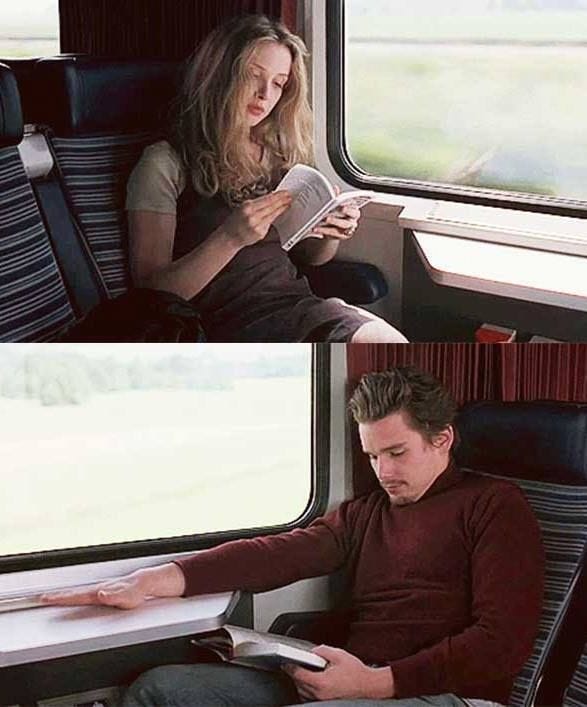

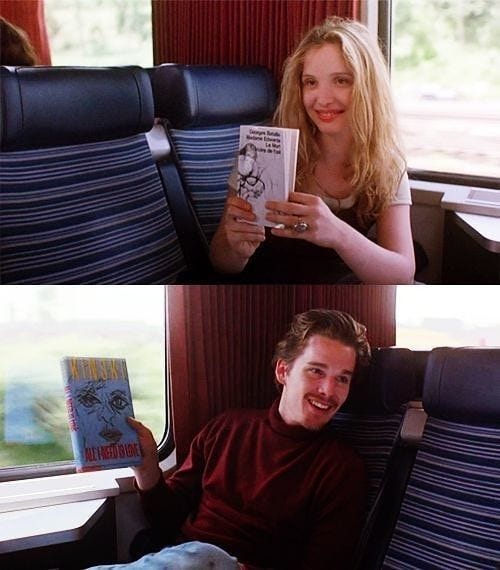

In this current piece, I want to look at the other, open end of this, that unusual receptiveness which is a characteristic of American culture, and which — in a nice Hegelian way — in fact enables its own opposite, the relatedness between complete strangers to come to exist. It is not by accident that in Before Sunrise one half of the couple is American. That night-long conversation and then eventual marriage would never have happened between two Europeans, no matter how cute or smart or interesting that boy or girl on the train was.

They would have just stayed like this:

📖 “STRANGER CULTURE”:

Behavior norms and social rewards encouraging and governing the engagement with new people for short-term or long-term cooperation.

A few years ago in The Atlantic, dear Olga Khazan argued that the reason why Americans smile so much — really no other culture places such an emphasis on public smiling, let alone the economic signaling of perfect white teeth in that smile! — is due to historical reasons. Long before American armies and pop culture would take over the world, the country — whatever some politicians today might be saying — was an unusually multicultural place, comparable really only to places like Ancient Rome, Greek Alexandria, or some wharfs around Empire-era London. As a result, in America, people from very different corners of the world would habitually find themselves having to trade or collaborate with each other somehow.

Their encounters, as we can imagine, were roughly as “monolingual” as when an expedition comes across a remote tribe in the rainforest: if neither party spoke any English yet or not well enough, the people involved had no language in common at all.

So how could one proceed? Well, by using any other means of communication: hand gestures, surely, pointing at things … but mostly the face. Lucky for us, the human face evolved for communication: our hairless, childlike homo sapiens countenance can show a million different emotions and intentions — our ape eyes are no longer black buttons but evolved a white sclera to emphasize the direction of our gaze, our stretchable cheeks and mouths can express a greater variety of feeling than even our words. We scan each other constantly for clues — we read some emotions in the eyes (dishonesty, desire, shame), while some others around the mouth (delight, contempt, sadness) without even noticing that we are doing it. Nothing alters the face more than a smile: it unites all parts, all muscles, the entire bone structure. When lost for words, the Babel-like American past had a toolkit to reach for.

In time, the open glance, reassuring nods, and inviting smiles — even a louder, more open accent — became cornerstones of stranger culture, the American way of being able to befriend strangers.

Enthusiastic, open-mouthed smiles would have come across as overly intimate or even idiotic to Europeans (until they fell head over heels for it, of course). In America they signal trust, health, and optimism. (“I am at home in the world.”) What American faces want to be, first and foremost is: inviting. Khazan recounts how, when McDonald’s first arrived in Russia, they had to teach the young people working there how to smile and make eye contact. These activities were not previously part of the cultural repertoire.

Many of my European friends would never come to America mostly because they don’t like Americans, seeing them as flighty and flaky. For them “See you sometime!” is a constant letdown: they really think they will see you at some specific time soon. I have never shared these worries which is probably at least partly responsible for how I ended up living here. In fact I love, in the most generalized sense, how Americans behave and how you build relationships here.

I have lived in five European countries in my life — four of those in Western Europe — and I like to tell my American friends that in none of those countries would I have ever so readily been invited to, say, a Thanksgiving dinner, like I was several times in the USA before even moving here, often by semi-strangers, often to events that included their families too. A formative European experience of mine was Christmas Eve 2018, when my two Hungarian housemates in London — sisters — were having Christmas dinner downstairs with their mother and aunt, and to my surprise I had to stay in my room alone all night (they counted the king prawns price per person, and instead of asking me to chip in £20, I got banished). Those of you who know me and my work are aware that I have pretty strong social competency and so these things didn’t happen because of some awkwardness from my side. This is just how it is in Europe.

When people tell me about American loneliness, they might be less aware of what’s really going on across the Atlantic which, in my 36 years of experience there, is way more pent-up, clique-y, and distrustful in nearly every imaginable scenario than social life in America. Don’t be fooled by the little groups around the café tables you see on your holiday in Paris: the amount of value — social, intellectual, economic — that is “left on the table” in Europe because free mingling is so culturally prohibited is hard to even conceptualize. Social violence in this sense really is economic violence; the artery blockage no one asked for. (We say “free flow” of people, goods, and information for a reason: our entire civilization developed around the great rivers — the Nile, the Tigris and Euphrates, the Tiber, the Danube, the Rhine, the Seine, the Thames — with populations moving up and down them with their spouses and wares. What happened?)

Americans, on the other hand, love to mingle (so much so that they invented the sitcom for when you can’t). My personal preference for the American way may be my legacy from Jewish culture where, regardless of which country your strand of the diaspora happens to fall in, association with other people is pretty much “on steroids” at all times, and where a large part of life is devoted to managing relatively new and very generative connections. In Jewish culture, where we place such a big emphasis on family and firm — a compensation? — in fact one’s home is just a small starting point for ever-expanding social exploration. A fun conversation to have with Indian-American friends is diving into the similarities — talk about another culture that is inviting — and why these two ethnic groups have done so disproportionately well in America. There’s a reason why we use the Yiddish word “to schmooze” in American English for a very specific type of activity — you know what I’m talking about — but we could just as easily use “adda”, borrowing from Hindi.

Having more people from more places around who all have similar sensibilities is the American superpower. I rarely hear citizens of other “new countries” (as we Europeans still like to call you) like Canada, Australia, or New Zealand talk about just how flexible and open-hearted their compatriots are. Quite the opposite! The deep similarities between Indians and Americans, on the other hand, and how Kiwis and Canadians might seem friendly but come nowhere near Americans in their extroversion and openness to experience, refutes the theory that this is just about levels of historical immigration.

Naturally, it was about America that the hypothesis of “weak ties” was first proposed in network theory. For people familiar with scientific and economic history, all of this sounds logical: the moment when Londoners switched from bad beer to good coffee, they suddenly decided to turn their social gatherings into a place for trade speculation and inventing stuff they could then sell at scale. This did not only greatly raise the immediate value of information — as opposed to seeing it as just an annoying source of doubt about religious or social doctrine — but demanded that systems be built for managing the information being thus generated and amassed. The fact that not so very long after this people built the first incarnation of a computer is not shocking: the curiosity and the greed had always been there (in fact curiosity is a kind of greed itself) but now there also was the promise of immediate, socially differentiating rewards. And so people both started associating in a different kind of way and seeking to move to places where this was possible. The places that allowed for freer association became rich in a very non-zero sum way (compare the Spanish crown money and cathedral system to London’s harbors and stock exchange, and guess which one had more dough 200 years on).

There are ideal equilibriums where multiple different factors both motivate and enable people to cooperate at wide scales — including the presence of political liberties, protections, and institutions, an expected standard for congeniality and output, and both economic and social rewards within reach — that happen to be present in the USA, high levels of immigration and then immigrant behavior being just some of these.

The schmoozers, as always, win by a landslide. Political systems that are low trust and slow information lag behind. And so it seems that balanced combinations of the hypomanic edge and great and satisfiable ambitions are what’s adding up into this unprecedentedly open culture, where I, for the first time in my life, feel like I never have to explain myself to anyone for whatever life choice I have made, whatever I believe, or whomsoever I enter whatever kind of relationship with. This to me comes as such a huge psychological relief that it overwrites a lot of other stressors — administrative, emotional, financial — that are also very present here.

Before we go into these, let’s look at some models that can help us understand stranger culture in America:

The “weak ties” theorem

In America, Mark Granovetter’s 1973 paper that describes weak social ties within social networks is considered one of the most important sociology papers ever written. At the time, social network theory mainly focused on strong ties between family members, married couples, colleagues, and friends, and how these worked. When I talk about new intellectual “clans” developing their own information systems in ‘American Catalysis’, that is not far from that. (Interestingly Goethe, oft-mentioned in my essay, was one of the first people to formulate the strong ties idea in Elective Affinities, a novel where, in the secret backdoor labyrinth of their mansion, a husband once famously gets lost on his way to his mistress, and ends up by accident in his own wife’s room. Oops. Strong ties.)

To economists such as Adam Smith, novelists like Austen, Eliot, Dickens, or Tolstoy, and political visionaries like Tocqueville, the fact that weak ties run the world was always obvious. While families, schools, sports teams, colleagues, and old friends form strong ties with each other, the ties that connect these nodes to each other are so-called weak ties. Starting a new business, making a new friend, marrying into a new family, a way for neighbors to make well-informed political decisions together: the success of all these actions depends on how well-functioning our weak ties are. Through our weak ties, every single family, workplace, etc., in the country is connected to each other. (“Six degrees of separation” was coined by a Budapest writer, by the way. No one meddles like we do!)

Without weak ties and the information exchanged through them, families could not hang out together, workplaces could not learn from each other, friends couldn’t make friends with their friends’ friends — sure, in some cultures you’re supposed to marry your cousin and start a business with your uncle, but when it comes to not the stability, but the elasticity and evolution of a society, those archaic conditions are not competitive. When an American family invites a stranger like me for Thanksgiving, and is willing to become friends with me and consider then nurturing this friendship in the long-term, it is because of their openness to forming weak ties, which may or may not turn into strong ones later on.

And that takes us to —

High trust vs low trust countries

My friend, the Budapest journalist Adam Kiss theorizes that between 1919 and 1963 every family in Hungary was destroyed. Whether it was the communists, or the fascists, or the communists again — and you wonder why we smile less! — someone at some point walked into your house and took you or your stuff or you and your stuff. When today Hungarians look around their own homes or at their children, and remember the family lore or the countless things that grandparents never talked about, the feeling in their hearts is not certainty or confidence.

During university, I once worked at an NGO that campaigned to encourage LGBTQI Hungarians to answer truthfully during the upcoming anonymous census. We argued, possibly living in a dreamworld, that representation would be more vigorous if the government had a clearer picture of just how many people in the country identify as what. LGBTQI community members knew better: they didn’t trust either the government or their method, and in the end most of them refused to answer this question on the form.

In the mid-’90s, when I was around twelve years old, I visited the wealthy Vienna home of my uncle, a talented tradesman who managed to get past the Iron Curtain before I was born, back when few others could. One morning, standing on a corner in their prim Austrian suburb, I saw to my great puzzlement that you could get the daily newspaper out of a pile and then place a coin into a jar after. I was bewildered. I asked my aunt: HOW was this possible?! Won’t the people just steal the newspaper?! Steal the jar of money?! And my aunt, a former top model with an economics degree who understands value very well, explained to me that Austria was both a rich country (no one wants a couple of coins) and one with high levels of trust between neighbors. No one will steal the paper and deprive each other — not to mention that if anyone started stealing, the news company would just remove the pile, and then everybody would have to travel to the newsstand much further away instead of getting the paper on their street corner.

When I moved to London and saw how some public utilities were not vandalized, I took note similarly: other than in some “broken windows” parts of town, people usually don’t want to deprive themselves of goods, and so they also don’t deprive each other that much.

When we model the types of cooperation that will happen in a society, we differentiate between low and high trust cultures. All societies have some areas that will be high trust. When we say “high trust society” what we mean is that in some exceptionally fortunate places, there is wide-scale trust even between people who don’t know much about each other.

Consider various levels and combinations:

Family

A low trust society might prompt individuals to stay congregated with those they are biologically related to. The old “dynastic marriage” effect is real, and people even in more violent living conditions will be less willing to hurt direct relations, the father of your grandchild, etc., as they would also inconvenience themselves. In certain countries, some people still think — despite historical evidence, a library of Shakespeare tragedies, and some famous Coppola movies — that “in business, you can only trust family”.

However stable family life might feel in these entangled old-fashioned kinship setups, they will always come with a high level of distrust toward outsiders, and thus prevent a strong stranger culture from developing. In some other places, stranger culture might be less visible, but you will notice a strong “guest culture” — is the guest God? — and in such places you can be sure there is a great interest in outsiders, partnerships, and trade, despite appearances.

Incentives

A tight-knit family that feels it is surrounded by enemies is a sign that society-wide trust is low. If families — or any other type of “node” — don’t have weak ties with each other, they will not feel like they’re on the same team, part of a bigger system together.

When you travel to Silicon Valley, for example, a place that can only really exist in America, you find startups that are existential rivals of each other. And yet they are so densely connected by weak ties — constantly hiring from, investing in, and merging with each other — that they form a very specific professional community. Every American startup feels they have a stake in how the entire future will look: these collaborative households all work on bringing about a technological utopia faster.

When you read tweets about how much support people in Silicon Valley give to entrants and colleagues, all the warm intros and the angel checks, that is because of this cohesion of vision. If somebody there is an infamous asshole, they’d better have a lot of FU money or else no one will want to work with them.

In a business venture where screwing over your partners will make you very rich and famous will make you less immediately cooperative than, say, in a war, where your platoon can only make it out of a certain part of the jungle or desert if you stick together. When people choose whether to collaborate, they look at the rewards and penalties for “defecting”: any cooperation will be higher trust if we feel that defection is not so easy and not so rewarding.

Emotions are great at bringing people together. In many life/death situations, you will grow to care for your peers deeply. In intellectually or artistically creative environments, where people undergo psychological exposure together, family-style bonds are also common.

People who were nurses, WAAFs, or emergency workers during major disasters or wars talk about how those periods brought together entire generations. Collective sentiments are world-changing, and the people who feel what you feel and risk what you risk will be people you will trust. In populist dictatorships, this collective sentiment is often manufactured (via threats, censors, enemy narrative, public celebrations). Interestingly, wide-scale trust rarely develops under oppression. More on this later.

High trust societies allow for free association and forming emotional connections with strangers, whether for short-term or long-term connection. A healthy stranger culture is a sign of a healthy society.

Religion

People talk about the “civic religion” of America: liberal democracy with its Washington DC temples and the adulating tourists waiting up the steps to enter and worship. I lived in France and, believe me, it can get worse: there is nothing like the symbiotic mania that most French people have for la République. The American Goddess of Liberty might be welcoming the poor huddled masses come rain or come shine, but I imagine few Americans have such hots for her as a Frenchman does for poor Marianne.

What makes the American civic religion so unique is that, unlike the French who technically swapped one god for another, American life can tolerate both Caesar and God; the devotion to the democratic ideal can coexist with a lot more actual religiosity than in Europe.

Christianity, still the dominant religion of America, has some very strong norms for stranger culture — in fact, consequential thinkers, most recently the historian Tom Holland, argue that many of our wide-scale cooperative, nonviolent, equitable norms descended directly from Christianity, a great break from the “eye for an eye”, brutal, ancient pagan world.

Christianity dictates a golden rule. Our scriptures and teachings place great emphasis on visitors and outsiders. The angels visiting Abraham or Jacob. The flight of Abraham, Lot, Jonah, Ruth, etc., and of course Moses, and their reintegration into a new place. The Good Samaritan, the Annunciation, Elizabeth. Mary giving birth while traveling. Not to mention all the people Jesus visits and all those who host him. There are visitations in ancient texts too, of course, in the Epic of Gilgamesh and Greek mythology, but they usually end with somebody getting raped.

The Bible, however, could be read in its entirety as a series of encounters between strangers who affect and collaborate with each other, become friends and save each other. “Angel” literally means messenger. “Evangelium” means good news. The strangers you talk to bring news, information. The Word travels.

“Guest culture” is huge in Christianity: “Jesus said to his disciples, ‘If anyone accepts you in his home, then he is also accepting me. And anyone who accepts me, also accepts my Father God, who sent me.” (Matthew 10:40. Compare with the Jewish mitzvah — commandment — of hachnasat orchim, “welcoming guests”.) Inventing email marketing, Saint Paul later develops exceptional weak ties between various Christian communities via his Epistles, and transcends the family-bound ethnic structures of Judaism forever. A global institution is built that is safer and more stable for everyone. At home in the world.

Specific Christian traditions are not the only reason why religion in America is such a powerful social glue. It looks like any religion that is being practiced will endow communities with higher levels of trust and satisfaction. Shared service attendance, the pleasures of music, and a general sense of moral reliability help strangers cooperate in stronger ways and feel like they have a kind of social insurance for hard times. (Ask your Mormon friend what happens when he has a leaky pipe or a sick child and needs help. People will show up.)

Group evolution theory argues that in early human history the tribes that were united by a shared belief system outcompeted their rival groups. The genes of the religious won and proliferated. Even if you’re a bigger atheist than Richard Dawkins himself, you and I are both descendants of countless generations of people who were very religious. And it is not just in the deep past. Even today, most major armed conflicts are religious, even civilizational. People are pretty touchy about these things, and few things feel as identity-threatening than someone forcing some faith on you or trying to take away your old one. And, since faith cannot be explained with rational reasoning, people can only rely on tradition and nobody questioning what they believe — arguments or ridicule will only be met with resistance to cooperation.

Religion that is left to flourish will yield a lot of social benefits: well-oiled strong ties, morally reliable weak ties, general good vibes. A condition to this, I believe, is that religions themselves develop weak ties with each other and with non-believers to avoid isolation, echo chambers, and fanaticization. It is good news that the current Pope and many other religious leaders are promoting this.

Democracy

We’re not going to try to summarize what democracy is and how it works in one paragraph. (Who do we think we are, ChatGPT?) Instead, we are going to note that in most analyses of high vs low trust societies (Fukuyama, et al.), the matter of self-governance is central.

Why is that? Well, as Tocqueville to his surprise discovered traveling around America in the early 1800s, people who are granted a lot of political, economic, and religious freedoms — people who are not oppressed or restricted— will somehow be able to trust more people in their society and at a wider scale.

If I get Tocqueville’s logic correctly, he argues that freedom gives people an ability to feel involved in all levels of the political structure — as opposed to feeling like my family / village / factory is on one side and the king / dictator / owner is on another and when they want something from me, I will be reluctant or only do it while internally resisting, cheating, or doing it badly on purpose. (Why Tocqueville also notes how autocracies bring their population into war more easily — by force — while democracies have to be very convincing. But once at war, democratic armies seem to be stronger and have higher morale, since the buy-in is real.) In Tocqueville’s description of democracy, we are all on one team, even if we disagree about politics — in fact we are on one team because we can all disagree about politics.

Feeling involved in all levels of the system makes people trust it more: now I can understand that the Vienna newspaper, while technically there for free for the taking, is there for me, and I will pay after taking one so it keeps coming each morning. In the Tocquevillian ideal of democratic equality, I see no qualitative difference — because there really is none — between the men and women running the country and myself, and so when I look at my home or my children it won’t even cross my mind that one of these leaders would ever come and take them from me. A citizen in a functional democracy looks at the student handing out the census form and knows he can trust her: her life in a democracy is not spent betraying her fellow citizens to gain the favors of some tyrant.

When today’s political agitators fantasize about popes and kings, they forget why we got rid of those forms of oppression and trust-killing in the first place.

Feminism, civil rights, social progress

You surely have noticed that open societies tend to be faster to [at least try to] adopt socially progressive norms. Universal suffrage, reproductive rights, desegregation, demilitarization, and so on appeared and spread at greater speeds in societies where free speech and technological-economic access to its results enabled people to communicate with and learn from each other better. Where political liberties such as freedom of assembly and free elections then enabled them to take whatever they have discussed and identified as a solution and turn it into action, policy.

We live under such fortunate conditions while elsewhere in the world ethnic groups are still kept in serf-like conditions, girls are denied schooling, sold for money, even mutilated; some parts of the population are not allowed to vote, and political speech and action provoke severe, often lethal punishments. There is no norm so abhorrent anywhere today that wasn’t at some point shared by many more societies, if not all. It took us a long time to get rid of them, and the places where they were successfully eradicated are today more open than the ones where they were not. A place where women can go to school and decide when to have children and by whom, where gay people can build a family, where religious or ethnic affiliation doesn’t bar anybody from partaking in elections, and where peacefully expressing opinions online or offline doesn’t entail punitive horrors will, quite understandably, be a higher trust society. And so high trust is like a virtuous circle: more trust creates more vigorous social negotiation, and the results of such negotiations create more trust.

High trust societies — like any high trust relationship, really — are also, always, more transparent. When, after joining the EU, Hungarian LGBTQI citizens became slightly more vocal about their rights and needs, many from the older generations were genuinely surprised: “Who knew that there were gay people in Hungary? Where are they coming from?” Some older people thought they somehow “became gay” overnight, because even that seemed more likely to them than the simple truth that for a long time so many of their fellow Hungarians had to live lives full of pain and risk in hiding.

The internet

The more time you spend on the internet, the more you will become an American. Internet users around the world constitute a virtual American diaspora. Their weak ties are hardcoded and unthinkably powerful.

The increasing openness and connectedness that the internet has brought about works in a weird way when it comes to social trust. From this angle, the internet seems to split social reality into two.

The wild thing about the internet is not just that it is by default open-borders and international, etc. etc. etc. — but that it behaves like a secondary country in every country. Even in America.

To people who don’t understand the dialectic, it will seem like there is an Offline America and an Online America, and that these two realms work differently and obey very different rules. The great politicization of the tech industry, which has been a staple of the second Trump Administration, could not fully close this perception delta. Like a static in an old phone line, the online world disturbs the information system that is liberal democracy. Yet without internet, we couldn’t call ourselves democrats: would we deprive the population of access to most of the information in the world?

So how to understand these contradictions? Let’s look at some of my favorite dichotomies here, and how they complicate low/high trust in society:

(1)

Having free access to the internet is in many ways a more immediate and important problem than even free speech.

While free speech is a core political right, access to the internet feels more like a human right. Not giving somebody access to the internet is like keeping somebody illiterate by force. It doesn’t just deprive you of social freedoms — it deprives you of your full humanity as an individual.

Those who want to take away your free access to the internet will use all sorts of comforting distortions to bypass your intellectual immune system: community “values”, children’s “mental health”, “necessary” regulation against Big Bad Company, “sacred” land inviolable by cables, employees shouldn’t get “distracted”, etc.

All of these are designed to make you feel dumb, guilty, or ashamed for demanding something that is your human right. Whichever pocket of the culture war you inhabit, please never forget this.

(2)

Having free access to the internet does not necessarily lead to a higher trust society.

For example, if you go online and find out just how incompetent your government is or how ill-conceived the opinions of other people are, that will not make you feel more relaxed about your new neighbors or the truck that just arrived to repair the pavement on the other side of the street.

That said — and despite the many dangers of misinformation — what the internet does do, and why so many people seek to limit, even dismantle it, is amplify the truth. Sometimes the truth is bad. Not knowing it is even worse.

(3)

What the internet does for trust is it enables you to find people to trust.

If you are lucky, and adequate online tools are at avail, a lot of these trustworthy people will turn out to live quite close to you. In some other cases — another form of potential luck — you will discover your “tribe” at some random faraway place or even scattered all over the world.

Platforms like my company Interintellect — a marketplace for hosting conversations about big ideas — demonstrate how, when they find their soulmate, a lot of people will in fact change jobs, move to a new place, intermarry, etc. Balaji Srinivasan talks about a “Network State”. I think there are also “state networks”: these — at first virtual — social structures behave like a high-trust country wherever the individuals happen to be physically located.

(4)

As I argued in my 2019 essay “We’re a Niche We Just Didn’t Know”, a piece that went viral and kickstarted Interintellect, in everyday life there is little use in differentiating between “online” and “offline” anymore. What happens on the internet shapes your IRL experience anyway, and what happens offline will end up online in some way.

A free press was intended to create a higher trust society: the powers that be were held accountable, the little guy vindicated. If you did something bad, everyone would know. If you were pretty or rich, everyone would want you. The internet does something far more ambiguous to society’s trust levels.

I have argued elsewhere that the Capitol Riots were a paradigm shift in American culture. They proved that the country had … shrunk. Before the internet came and enabled us all to feel so close to each other, America felt bigger. If you didn’t like it somewhere, you could pack up your things — your spouse and your wares — and move to a completely different part of the country, into a different version of the culture, a different geography, a different climate, a different time zone, even a different language. My late father used to say that is why America never had Europe-style revolutions: you didn’t have to keep looking at the people you didn’t like if you didn’t want to. You didn’t have to deal with everything that was going on everywhere on a daily basis. But this is no longer the case. You can’t just pack up your things and move across the continent and never deal with whatever or whoever you left behind ever again. In a dialectical way, the information expansion the internet has unblocked has made the world — and America — a smaller place.

Even if access to the internet is a human right, you can’t call yourself free, you can’t see your choices and associations as free, if you cannot leave.

When people talk about curation and taste being the art of the future, their intuitions are correct.

*

Without high trust in a society, there can’t exist a healthy stranger culture. Encounters with the Other will be seen as unnecessary, suspicious, undesirable, or even dangerous. One thing pagan Greek texts and the Bible both agree on is that strangers are information: they always bring news. New gossip. New ideas. New inventions. New challenges.

Societies that are open and trusting will be open to integrating new knowledge. But only on their own terms and willingly.

Low-context vs high-context cultures

Let us go back to your smile for a moment. As first proposed by Edward T. Hall in the late ‘50s, communication theory differentiates between low vs high-context cultures.

To use a simple example: a toddler who has spent every waking moment of his life in the company of his mother will only need to say something like “kha—!” and the mother will know that he means the little red toy car that fell off the shelf five hours ago in the other room. She has extremely high context, and rudimentary, fragmented, allusive communication will suffice.

Another example: when leaving the movie theater, your friend jokes that the actor has huge eyes and looks like a fish. Hours later, when paying for dinner, your friend makes a funny fish face, and you both burst out laughing. No one around you understands what just happened, but you two have context.

On the other end of this spectrum is a camping site in the middle of Kazakhstan, where a clever entrepreneur will make sure his tea station is clearly signaled, otherwise the hikers would not know what the little shack is and would not stop, thereby ruining his business. Such an establishment will likely feature a sign in English, some kind of illustration of a steaming tea cup and a thermos, and several arrows. Maybe — why not? — the logos of Visa and MasterCard. Come on in…

During the pandemic, we all saw new levels of low-context panic. The creative ways in which illustrated guides on walls were asking you to wear masks, wash your hands, and please don’t spit on each other were both alarming and hilarious. But even without murderous viruses, busy multiethnic hubs like Brussels or the cities of America will display instructions in two or more languages — in Belgium French and Dutch, in America English and Spanish. This is another example of low context: whoever wants you to do what the sign says can’t know in advance whether you speak the main language or not.

Low context culture is in many ways stranger culture. Facial expressions, gesticulation, an inviting conduct — these are fundamentals where context is not expected to be shared. A friend of mine once looked at a couple, our friends, across our lunch table, and quietly remarked to me how she was sure the couple was about to break up, because they were so polite to each other. She was right. Etiquette — from domestic to highest level political — is a language of the low context: whatever guest might join your barbecue, whatever delegation might attend your state dinner, there is a shared set of customs to make the experience hopefully enjoyable for everyone.

In some European cultures where, unlike in English, we have formal and informal words for “you”, people used to differentiate even within their homes between high context and low context spaces. In the age of the Hungarian gentry, for example, even a husband and a wife would address each other formally in the shared rooms of the home — the salon, the dining room, the ballroom — while more personal forms of address were only used in the private quarters. As my aristocratic godmother once so eloquently noted, du/tu were for “Fuck you” and “I want to fuck you”, for everything else you leave your gloves on and behave comme il faut.

The Herculean task of any low context culture is to bridge communication gaps and enable strong, deep, lasting relationships to develop. The higher the openness of a culture, the easier this will be. Being open to new people to whatever degree you see personally fit grows not just the number of potential short term or weak connections but also the number of potential long term or strong ones.

Low context and high context forms of social violence also diverge. High context is full of emotional abuse and linguistic attack: in a family, a marriage, between old collaborators the participants always know how to hurt each other the most efficiently, where the pain points are. It takes a blessed saint to always resist and not poke there, although mutual deterrence does work. In a low context culture, on the other hand, people will be seen as “types” and aggression will be played out on the group-level. Think sexism, racism, or hating a specific religion or sexual orientation.

The mores in low vs high context cultures also work differently. Low context cultures produce superficial social butterflies and chronic philanderers, low context being ideal for “getting away with it” and “never having to face it”. Who would hold you accountable…? In London, Tinder is the app for fooling around. Even when they want to, many people will simply never be able to see each other ever again, given the size and chaos of the city. In cozy Budapest, people get married on Tinder. It’s a small place, everyone knows each other, and there aren’t many things you can do that people won’t find out about in 48h at most.

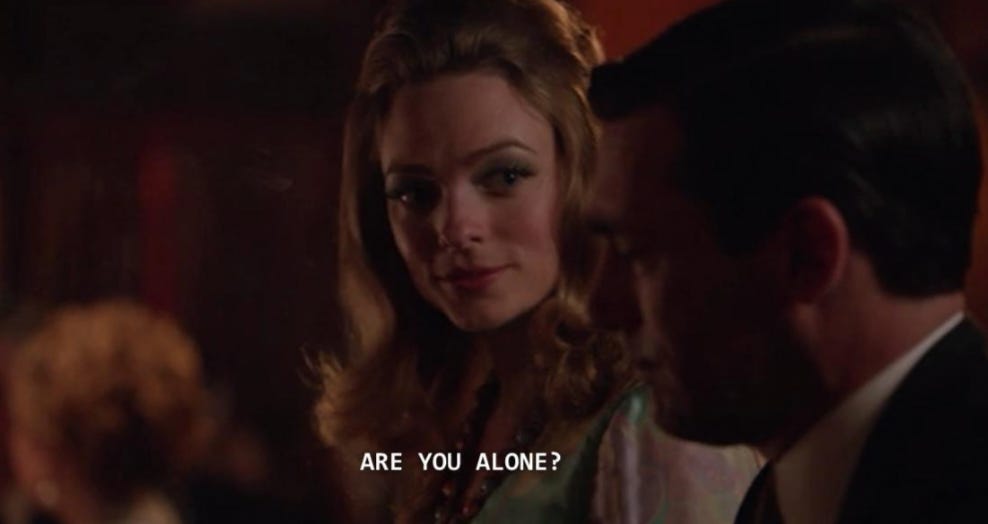

In my “Catalysis” essay, I discussed the TV series Mad Men at some length as an important comedy of manners for understanding identity, creativity, and talent in America.

I mentioned how, when his protégé Peggy temporarily detaches herself from her mentor Don Draper, she tells him: Don’t be a stranger. And you can see that I’m using a still from another legendary scene from the series as the header image of this essay, and you’re surely guessing that is not just there for decoration. You are right. Don, the story’s protagonist, arguably a stand-in for the show’s writer Matthew Weiner, is one of the most perfect embodiments of stranger culture I have ever seen. Of course he works in advertising, this most American of artforms, the artform of the low context: you don’t have to know anything about what this foaming detergent was doing in the past, the whole point is that it is — NEW! — exclusive!! Look at this smiling housewife on the billboard and her shiny washing machine! You understand her, without any context. She’s at home, in the world. And so are you.

Weiner even said in an interview, when answering viewer questions about some professional subterfuge or marital infidelity undertaken by Draper: “He likes strangers.” Wiener doesn’t say: Don prefers strangers [to those he already knows], but I think that’s what he means. Obviously, preferring strangers to the people one is deeply connected to and loves is pathological: only engaging with new people ensures no one ever gets to know you, ever gets to see the real you, and that you never have to deal with whatever you’re trying to escape from. To new people it is so easy to lie, to act. People who only have superficial friendships have no friends. People who sleep around for “variety” really only sleep with the same person over and over again. They only see the beginning which is always low context and thus always the same — no wonder they burn out.

While it would be less exciting in a TV series, in a healthy stranger culture we always strive for building something for the future. An invitation is not a goodbye. We open toward new people because there is a potential for more, otherwise it will feel like running around in a circle, as opposed to including a new person in our circle.

Building relationships from encounters with strangers is easiest in a low context + high trust environment — a stranger culture.

“From scratch” cultures

Imagine you were born in Rome on April 21, 1995, in the Trastevere neighborhood.

Your parents are super happy — a new arrival, new life! Your dad is singing adorable cheesy songs, and your mom is being showered with flowers and gifts from friends and coworkers. Your grandmother finds your mom’s old baby rompers in an old closet for you…

As you start growing and learning about the world, you learn that you were born into a 3,000+ year old culture, into a beautiful, old city that is also the seat of the leader of an old world religion that determined your birth date to be “1995” to begin with. While you will hear a lot about city states, fleeing kings, dictators, world wars, political corruption, and an immigration crisis, your world appears complete and pleasing. The environment is welcoming — so much so that it is teeming with tourists — the language and the literature are beautiful, the art mindblowing, the food delicious, the ways in which your country contributes to industrial design and fashion commendable, and you will even be able to access a nearly functional social welfare system.

When people ask about innovation stasis in Europe, I always imagine this girl — now woman — in Rome, and how marginal her prospects can seem. Things being as old and OK-looking as they are, she will have very little incentive to try and disturb or subvert her system. She would certainly get no rewards for it (not unless she went extremely online). Unlike in other old cultures like India, everything around this young Italian is almost complete (“almost” either because unfinished or because beyond its zenith and decaying). And so she is not so interested in disruptive information, in mingling with that many new people or learning how to appear inviting to them. She is a character in a play already written. Maybe there will be small things to move an inch to the left or to the right, but she might not crave — in absence of encouraged ambition or dire necessity — all-transforming change.

Or if she does, she might end up moving to the USA.

Come to the USA where nothing works, and where, if you want something, you might as well build it for yourself. There is a great power to this instability: no wonder so many new religions, subcultures, artistic movements either developed here or came and found a home. In such a “Zero to One” country, you will need collaborators to accomplish mere basics, and you will trust the kindness of strangers. You will have to. When people move to Bordeaux or Oslo and lament how everybody has a handful of friends all their lives and they all met in kindergarten, making it impossible for outsiders to enter their circles, what they are noticing is a lack of need: the locals of Bordeaux or Oslo are just fine, they don’t need to bring new people into their lives. There is no need, no danger, no great reward to motivate you to learn the art of openness. Those who know and love practicing this art will feel claustrophobic and bored to tears, and they will move their wares somewhere else.

And so while I share the great concern about American loneliness, it should fill us with some hope that if you’re lonely in a stranger culture, there is at least a chance to start building the community you want from scratch. In America, people will show up, raise the barn with you, and maybe even stick around for you. Just as it is in Jewish culture, where no diaspora can ever truly take their social network for granted and so you continue to work on it day after day, it is part of the American ethos that if you want something to exist, you will likely need to do it yourself. As the Hungarians would say: hunger is the best cook. (In India, another old but still hungry culture, you sense a similar restlessness.)

In my “Catalysis” essay, I explored encounter, inspiration, and mentorship — and called mentorship one of these “from scratch” types of relationships, where a lot is at stake and emotions can run wild, but where stable and productive one-off structures can arise from how the participants choose to shape their relatedness. That kind of weighty flexibility — both up in the air and vitally basic — is greatly catalyzed by stranger culture. It requires transgressions not so possible in closed societies: long term correspondence between people who have never met, semi-strangers flying to another continent to hang out with each other, unattached men and women out in public spending time together, friendship between young and old who aren’t family, the wealthy and the destitute in conversation without any agenda other than learning. When I talked earlier about “value being left on the table” in societies that don’t permit such relationships, this is what I meant.

But from scratch relationships are also risky. One thing I find concerning is the question of —

Irresponsible people

An attitude that seems to naturally arise from the combination of (1) low context + (2) high trust + (3) high openness + (4) “from scratch mindset” that together adds up into stranger culture is irresponsibility.

In the culture that is America, a lot more people will want to get involved in your life and with a lot less information about you than any European would dare to venture. This is great for innovation, association, collaboration, and community building. But it is its own kind of grave danger when it comes to major life changes and commitments.

In Europe, too, people can say a lot of unfounded things about each other in very specific situations — an obvious such situation is seduction. As a young woman, a cavalcade of men told me I seemed “withdrawn”, “too extroverted”, “thoughtful”, “thoughtless”, a “prude”, a “clearly very liberated young woman”, “boring”, “crazy”, “talented”, a “dilettante”, “oversensitive”, and “heartless”, and many other rigorously researched and double-checked takes that hoped to impress a débutante with the depth of their insight. (If a young woman listens to all the nonsense men say about her to catch her attention, she will end up developing at least eight personalities, which is what actually happens to many of us.) The reason why Americans spend so much time on self-branding and self-categorizing — something that I still find myself quite terrible at — is because what would unfold only at a bad date in Europe is an integral part of everyday life in America. People constantly have opinions about each other based on very little data, and — oh — they will share it. The reason why people self-brand so vehemently here is because if you don’t classify yourself, someone else will do it for ya. This “telling you who you are” move is especially problematic when it is positive. Being positively misunderstood is its own kind of hell.

The irresponsibility of advice-giving in America is a complicated matter, because advice you do need, help you do need, friends who are interested in your trials and tribulations you do need. But in the great Human Comedy that is this great country, typecasting is real and low-information decision-making is encouraged. No wonder the self-help book industry was born here, no wonder the Twitter hot takes originated here. The ultimate form of low-information advisory is the advice column, the bullet point list, the productivity superstition. And so in America you are told that you can be anything, that you must move to San Francisco, that you should take amphetamines, that you should drop out of college, that you should take testosterone, that you should get a PhD, that you should inject nerve-poison into your face, that you should get a stable job at a FAANG company, that you should have three kids in your twenties, that you should stick a piece of metal up your cervix and leave it there forever, that you should buy ETH, and that you should try this unknown-origin Chinese weight loss tea that comes with a hazmat suit (look, one person gave it five stars before they died). Start a company! Make it a nonprofit! Try this cocaine! Raise venture capital! Relocate to Austin! Get a publicist! Take up student loan! Build a new city! Try polyamory (but just with me)! Sleep ten hours every night! Buy property! Get your knees replaced! Invest in lithium-ion batteries! Accept Jesus in your heart… Do what I do so I don’t feel so bad……… Hire me! Tattoo me! Marry me! You should write a book. — You should move to America. — If identity is a consumer good, it is good to remember that some decisions are not reversible, a problem at the heart of the trans debate.

America’s success is survivorship bias in the best sense: so many people here do so many dumb and irresponsible things that — thank you, statistics — some of them must work out. Enter the venture capitalist, the talent agent, the divorce lawyer.

And so in this great openness and information exchange, and my own great hunger for more, it has been my constant worry that people might have a tendency to be very irresponsible with other people’s lives, exerting conscious influence without asking too many questions or gathering enough data first. In Europe, people judge each other based on too much information. In America, you are judged by very little information. I think this is a logical byproduct of this country’s looking-ahead mentality. Background information, your past, is meaningless, it only matters insofar as it determines your “brand” which then will determine which future you can get. Like in screenwriting where the rule is that every scene must either move the plot forward or reveal character. You only need to show the audience so much of the character that will be enough for them to accept the character’s next move.

Much has been written about the “warm intro” as it is practiced in our industry. The warm intro that drives so much of American intellectualism and innovation — impossible in, e.g., England outside oldboy networks, and a different type of social flex in Budapest — is positive irresponsibility. People don’t warm intro their dearest cousins: they warm intro people they barely know to people they know a little bit better. Sending a “Please meet Anna, she’s working on something AMAZING” email is a rash decision and a formidable way to do business.

I love stranger culture but I think there is much more to people than their first impressions, their beginning. Europeans can get stuck, sure, but within those fixed structures many deep feelings can be cultivated. Maybe this is the social knowledge Europeans can bring to the great American mix: the skilled management of deepening, existing relationships — the engineering of the river system. Whether one ends up going to a deranged Nordic spa to reinvent a childhood friendship or not, we have seen in “Catalysis” how American life allows for the building of ad-hoc nonbiological collaborative clans that last. This potential for flexibility + loyalty is a public good.

Too much emphasis on beginnings is too much emphasis on what is unfair about the system, too. Consider how, for Americans who come from difficult or unprivileged backgrounds, being denied even a first impression can be a social disaster, an exclusion from the countrywide dynamism that is stranger culture. Stranger culture done well is an accepted invitation: at the start the context is scarce and the relations are archetypal. But do stick around for when the real human nuances, the idiosyncrasies and foibles, the complications that make us human reveal themselves: that is where people get really interesting.

I know there is a midway where the opening is active but where people don’t get flattened into bland 2D cutouts. I know because I have been there and I loved it. Friendship really is only possible in 3D.

A crucial life lesson in America is that with all the schmoozing going around, some people will — despite their best intentions — be irresponsible with your life. It is not a political statement but my takeaway has been that I am the only person who can truly be responsible for me. That I need to connect, yes, but also to curate. The recipient of the warm intro will be discerning, and decide for themselves whether Anna really is working on something “AMAZING”. Before you incorporate, start planning a wedding, or ink a two-foot dragon into the skin of your back, you will stop to consider why this person has given you this advice, and just how much context they really have.

And as Tocqueville and every VC knows, the best way to make somebody behave more responsibly toward your life is by giving them a stake in it, by connecting your lives together, whether with weak or strong ties.

*

Working on Interintellect, I am always surprised when two Americans who are well-known in the same field have never met each other before their Interintellect salon or festival appearance together. This is not something that would be conceivable in snug, intertwined Budapest. But even in London the professional community is small, everyone went to one of two universities, the number of people and configurations is low.

When my fellow Europeans see Americans as “flaky”, what they might not see is that Americans are socially busy, they’re actively in touch with far more people than Europeans tend to be, and they embark on real friendships with far less information. To this day, every once in a while I find myself mystified about whether this or that person on my internal list of “the twelve people in the world I care about” is or isn’t indifferent toward my person, and I know what I am reacting to is this numbers game being played. Big places have many people, and America is a very big place.

In the periods when I travel a lot and stay in a lot of Airbnbs around the US, I always arrive home with some fresh idea. Seeing how so many other people live is new information. What if I moved the kettle over there? What if I bought a salmon pink pillowcase? That cute little lamp… Encountering many people is another way of encountering many world models that people hold, many lifestyles they have chosen. The word I use a lot in America is indeed “discern”. Carving out your self from a far greater spread of fabric.

In the abundance of America, the great curators win. (As in “Catalysis”: connection + curation.) People who can discern. What is real. What is useful. Which person is for me. What advice is relevant. Who do I want to be and whom can I be. People who lose their heads will become strangers to themselves.

High variance experiences

Even if you have exceptional curatorial instincts, one part of life in America will continue to pose inevitable challenges: rejection.

We dealt with the biological and psychological effects of social rejection in “Catalysis” — being excluded or at least not being included, not being invited, causes great physical and mental stress to humans. This goes way back: homo sapiens evolved in groups and for groups. Feeling a part of it feels existential, a matter of survival. Yes, it will come into conflict with several other human desires, such as the one for spiritual autonomy (people don’t like to be converted to faiths against their will so much that they will start wars), individual differentiation (people don’t like to be mistaken for others or to feel replaceable), or free association (people like to choose their friends and lovers for themselves, and want to be individually chosen and loved).

Rejection and curation are therefore an epicenter of the human story, the eternal tradeoff between what is good for my community vs what is good for me. It runs from Cain and Abel to John Stuart Mill to George Eliot to Karl Marx to Milton Keynes to It’s a Wonderful Life to Casablanca to Miss Americana to whatever in the world made Ross and Rachel break up.

But rejection has a cultural impact too. Human history is the history of the rejected. Second sons rebel. The deplorables deplore. The marginalized social groups gather strength in the shadows and then rise up. Since I cannot prove a lover …. / I am determined to prove a villain. Every startup is a complaint. Every piece of writing is revenge.

Stranger culture — social ambition on steroids — is ripe with rejection. I noticed that I have a very specific form of depression that I only feel in America, and after years I have deciphered it to be simply … pain caused by rejection. In America, I am constantly rejected. I am, because I constantly try. There are things and places and people to try here, and so one does — one expands and goes on quests! Stranger culture is its own form of variable reward. There is a great variance of experiences here. Some are truly terrible. But when it is good it is really good. The good stuff really comes out of trial and error and so it will be much better than most things handed to you as obvious in more closed societies like Europe. The hypomanic edge is also edgy hypomania: the amplitude of social contact is off the charts.

Of course, there is social rejection in Europe too, but it works differently. In Europe, your arena of social exploration is quite small, and so in a cyclical way you frequent only a handful of people at a time. These people, to make it a little bit more interesting, will sometimes want you and sometimes not. Your rejection will come from the same place as does your being accepted. To me, this has always felt super pointless and tedious. Like recreating high school for adults.

In America, the rejection comes from new people you are trying to connect with. It either comes right away — then you can continue working on being accepted, and sometimes you eventually are. Or it can come after the initial “first date” stage, when somebody sniffs you out but then thinks you’re not a match, or when you’ve had your “one hit wonder” but now you don’t seem that promising anymore. In almost all such cases, you can make a comeback if you try hard.

Socially, Europe vs America is like playing one chess game vs simuls. In my experience, in the nice Tocquevillian way, once the choice (connection + curation) has been made, freely and from many options, these voluntary American or American-style relationships tend to be stronger than the ones one is born into in Europe.

And maybe it’s just me, but isn’t it more fun to have more chances?

A lot has been written about specific groups that feel rejected and therefore depressed in recent times. Peter Thiel famously spoke about why Millennials check out of capitalism. Peter Turchin identified the components of how counter-elites form in modern politics, blaming elite overproduction for the mating and labor market failures of the overproduced elites.

When we talk about vibecession, negative social contagion, and mental health crises, a useful approach is to think about them in terms of rejection. And to conceptualize rejection as a necessary albeit excruciating part of all free movement and free association, of stranger culture. I wonder whether how I have been teaching myself more resilience in a social world with so much freedom and choice to combat my rejection-fueled depressions could have a collective equivalent? Can social groups learn to accept the pain of failure as a normal part of trying and expanding? Are these, in fact, growing pains?

People love to claim that men are better at handling rejection, and base this on how — traditionally — men were supposed to have hit on many women at bars as a way to play for large numbers and put up with being turned down (or worse) until someone would agree to go home with them. But if you look at the types of social webs that women weave and then maintain, and how disproportionately job loss affects men’s mental wellbeing, you will realize this is a bit more complicated than that. I can’t see how groups could build resilience and enjoy freedom more without at least an inter-gender, but preferably also an intergenerational, exchange of ideas.

It is impossible to live in America and not know that freedom is very hard. Living in a social system that allows you to try again, though, makes it worthwhile. And if your future depends on whatever you are being typecast as by yourself or by others, you’d better fight for a role in the Human Comedy that allows you multiple attempts.

*

When we talk about superficial typecasting, we must take a moment, like we did in “Catalysis”, to talk about fame.

In many ways, fame is the ultimate stranger culture. A great number of people feel they know famous people. When people in America want to become famous, they want to become the “go-to guy” in a genre or field.

The part of stranger culture that is fame has a parasocial quality of course — people imagine they have a connection with famous people they’ve never met. But it is also true in the sense that running into celebrities is memorable. I am quite sure every single waiter who has ever served Quentin Tarantino and recognized him says they “met” him. I am pretty sure 20 years later Tarantino speaks much less about such an encounter than the lucky waiter does. (I hope Tarantino tipped generously!) And most celebrities have varied international schedules too, during which they end up meeting far more new people than most people do. When famous people burn out, they tend to become misanthropes. In fact I know very few older famous people who are not misanthropic to some degree.

All of this works in relative terms, of course. If you are the mayor of a small village then those 2,000 people in your jurisdiction will have this kind of imbalanced relationship with you (and your burnout will be caused by those 2,000 people).

In default stranger cultures like the USA, celebrities are a type of Schelling point between unrelated individuals. Whoever you are and whatever you believe in, you will probably have an opinion about the Kardashians, the Obamas, and some famous athlete I have never heard of. Celebrities in this sense are a bit like historical events or the government. I assume that in America, you can walk into any diner in the middle of nowhere and strike up a conversation about how lovely Dolly Parton is, how expensive everything is, and where everybody was on 9/11. The much written-about death of monoculture does not in fact diminish this effect at all: people, things, and events that are truly famous reach much wider audiences today than they ever have before.

In Europe, people want to become famous as a way to meet more people. I am a child of two generations of Budapest celebrities, and I can tell you that my parents — and I assume my film star grandfather too, although he died in 1968 and so I could never ask — knew way more people than anybody else I knew. For people who dislike silence and stasis, common elements of European life, building a public profile is an enticing possible way out.

In America, everything being downstream of connection + curation, people like to build their personal pantheons of which celebrities they personally like. On dates, “favorite this” or “favorite that” seem to be standard questions, a matter of identity. In the great openness that is fame culture within stranger culture, we want to form stubborn attachments even with our parasocial relationships. “Kanye is going through some things right now but I still love him.” “My team is going to win again someday.” It is not an accident that even mattress salesmen and injury lawyers pose as celebrities in commercials and on billboards here.

As I discussed in “Catalysis”, some parts of the tech world seem to be uniquely resistant to the temptations of fame. While there are some outrageous outsize characters out there of course, many of the truly powerful people in Silicon Valley you have never heard of. And yet the place is densely and proactively interconnected with millions and millions of weak ties. As a matter of fact, being too famous is seen as a complication in upholding these productive connections.

With my therapist — also from the Budapest “Jewish Mafia” — we often talk about my great desire for what Hungarians call the “szakma”. There is no good equivalent for this word in English, especially when used so metonymically. Szakma means trade, profession, a sector, an industry. And we use it also to denote the professional community of weak ties and friends. Respected by the szakma is what you want to be. Having grown up in show business, this specific feeling — of camaraderie and creation — has always been my expectation baseline, a kind of life goal (never money and never fame for me; always “do people want to work with me, do they want to be friends with me” — and I do think this is what everybody, really, wants).

To me, the American way of doing it feels very comfortable. In America, you don’t need to be either related or famous to have people know you, and to exercise your right to form newer and newer connections. Being only famous in the “szakma” is actually an excellent compromise where you can be a little bit of a Schelling point for others without too much of the public hassle. In many ways, Interintellect is a semi-public arena just like that, nestled between the brutal limelight of fame and the namelessness that feels to people like rejection. In the middle there is curated connection that lasts, as well as innovation and evolution; you can take responsibility for yourself. It’s in the middle where the really exciting things happen.

The stranger culture which catalyzes unprecedented levels of innovation in the intersection of America and the internet (Silicon Valley) but which also begets loneliness and injustice because not everybody, always, can build the basics for themselves, finds a balance in the middle.

Funnily, in America, where once again I spend so much of my time around very public people (how does this always happen to me?), what I have learned not through their advice but through their behavior is that in fact I love my privacy very much, and have little need for exposure beyond friends and “szakma”. This is what you get, I guess, when you send a Hegelian e-girl to America.

Life: changing

In 2012, I had to attend a series of European film festivals. I had written a couple of screenplays, and I was being selected into screenwriting labs with them, and shopping around trying to find a director. This was not so easy because in Europe the mostly male directors prefer to have at least co-written the screenplays, and I had no interest in directing a movie myself. And so I schmoozed and schmoozed a lot, in arctic Berlin and river-damp London, and pretentious, pointless Locarno, and for the first time started working with Americans more seriously.

I loved it. It was as if a giant weight that I had been carrying my whole life finally rolled off me. I could laugh loudly! I could say what I wanted! I could show interest and enthusiasm which are so important to me. I could sit down and walk away whenever I pleased. There were no mocking downcast eyes, no icy silences, no high school whispering about you in front of you. Americans looked at other people with an open face, and listened as you explained what you were working on. It was amazing! I was so happy that multiple times I nearly cried with disbelief and relief. In my heart I always knew it was possible, and now here it was. (You don’t have to hurt each other. You can, but you don’t have to.)

And at the festivals, my college years spent managing underground rock bands paid off big time: I knew all about how to end up at the wildest after party with the most shamelessly famous people, and how to leave unscathed…

Then I flew home. I was excited to use my new skills, my new freedom. One particularly warm night in August, I was hanging out with a friend in one of Budapest’s trademark ruin pubs, nursing our fröccs. It was late. As my friend and I were chatting into the night, I suddenly noticed that under the dark trees, at the next table about five feet away from me, a little group was sitting. I recognized them. A well-known Hungarian film director with whom I had just had a meeting about my script! He wanted to turn it into a Mad Men style TV show. A female film producer who had a reputation of being difficult, but whose team I’d had good experiences with and whom I had previously run into here and there. And a TV presenter looking to break into the film industry who had received my script, and we had been emailing about it that very morning and were scheduled to meet up soon.

It was clear to me that I couldn’t be sitting so close to these folks — all of them aware of and interacting with the Berlin Film Festival script lab selected historical movie that I had written, one of whom I hadn’t even met in person before — and not go over to say hi. But stronger than my sense of etiquette was just my simple happiness at the sight of possible future colleagues. And so I sat there and thought to myself: “I’m going to go and talk to them.”

I explained to you earlier in this essay how my social experiences have been very high variance because I expand and try a lot. That I have been actively looking for environments that enable, even reward this. That the price to pay for being able to start again is instability. Freedom comes with rejection. You open. You curate. You care. You win, or you lose. Then you try again.

I put down my fröccs, told my friend that I’d be back in a moment, and ducked under the dark trees. The other table immediately went quiet.

“Hi!”, I said.

Nothing.

Silence.

I froze. I, I … I explained how I was sitting just there, over there, hi, hi, and oh hi, and so great to meet XXX in person, does he want to talk …. a bit?

More silence. The female producer smirked. The famous director looked uncomfortable, he seemed to pity me for some unclear reason. The TV presenter stuttered something in a mocking tone that I couldn’t quite catch.

I just stood there in that tension and I didn’t get it. These people also went to the same film festivals, no? They must know how to not be like this. And why would complete strangers at those faraway film festivals be more friendly to me than the people of my own city? What makes my city so … small?

Eventually, the TV presenter somehow deigned to have a drink with me and talked to me for the ten minutes of our exchange like I was a mentally deficient five year old (which made me feel bad for any five year old he might speak to). I was shocked. I had lived in that city my whole life, for nearly 30 years, I hailed from a pretty prestigious and well-connected family with plenty of social capital and cosmopolitanism, and still they can do this to me. And why?

I never found out what I did wrong by walking to that table, literally three steps from my own. I had not read Girard yet. I have been humiliated — even violently attacked — a couple of times in my life but there was always some reason. This moment lives on in my memory as the most unnecessary slaughter.

After this, I started paying attention to silences in Europe. A week after my ill-fated ruin pub run-in, I attended a garden party in the home of my school friend Julianna. In her idyllic cottage on the outskirts of Budapest, many of our former Catholic school classmates gathered. I always assume that religious people will be kinder and I am always disappointed.

As we were eating at Julianna’s long rustic table, I got bored of the monotony of the conversation and made a joke. It wasn’t in any way political or sexual — I wouldn’t dare. Just some irony. Silence. People looked down. More silence. It went on. I looked at Julianna: WTF? She’s a clinical psychologist so I thought maybe she knows? (Later she explained to me some theory about how being insecure makes people mean. OK.)

The general sentiment of social life in Europe — Southern Europe’s cabals, France’s cutting sarcasm, England’s family tree paranoia, Eastern Europe’s hatred of being seen trying — is “I don’t know what I did.” You never know. They don’t tell you.

They don’t tell you because illegibility is the goal. They don’t want to identify, communicate, and then solve problems. While big open society America’s social rejection is a matter of numbers — in America and on the internet you need to try and find your people to love — European social circles are small. The only way to make the small, finite pool interesting is to accept and reject the same people for no reason on and off. Instead of finding variance in expansion, the law of diminishing returns applies. To my mind, it is inane, a waste of time. It blocks the free information flow, weakens social foundations. To me, it kills trust. To them, it feels like a sort of faux-freedom.

The way small children reject some foods because they feel powerless and the only thing they can say no to is what’s on their plates, if you’re forced to spend your life and career locked into a circle of 40 people, you will entertain yourself with always being socially violent to a random set of ten of them. In places where the work is hard and the walls are high — distance, cultural heterogeneity, atomized society — you will build with all your strength spaces and communities that are inviting. You will want to break down walls. In places where the work is easy, holidays are long, and everyone is thrown on top of each other anyway, the context is too high and so people will manufacture walls. In Europe, randomly rejecting people but not revealing the reason for their humiliation allows you to later “forgive” them or pretend you weren’t mean, and to reshuffle your love/hate matrix at will.

In America, “saving face” is equally important but seems to work differently. I am still learning this. I have had few open conflicts with Americans but in each case people came across as very “learned” about conflict resolution, this seems to be something that people are taught and that they practice. These discussions — except one notable case where I just told somebody to kindly fuck off (and I meant it) — always focused on problem solving and finding some compromise. Americans seem to always want to allow other people to “save face” so in the future there could be collaboration with them if necessary. I am new here, but this seems more rehabilitative, more about new chances. In Europe, everybody’s walking on broken bones all their lives. And you never know what you did — because you did nothing.