Private Kingdoms

Why you should make the public more democratic, and your home less.

“Every soul is like a minnow

Every mind is like a shark…”

Thresholds

It is easier to change the culture of an entire country than it is to change the culture of one family. The mysterious differences between how people function in public versus in private have always fascinated me. Growing up during the last years of communism in Eastern Europe and its aftermath, I noticed early people’s mistaken assumption that they can restrict their political freedoms and truths to their homes — where you can speak more or less openly among trusted relatives and friends — and perform the empty motions of socialism and later faux-democracy out in the public square, rituals that nobody seriously believes in. (For a good primer on how common knowledge is destroyed or prevented under oppressive political systems, you can start with Scott Aaronson or Václav Havel himself. I also wrote about this some years ago in more detail.)

A place where people negotiate their private and public truths, to increase the legibility of their values as a society and their sense of integrity as individuals, is the ill-defined “semi-public” or “third” space: the realm that is not exactly public and accessible to all, not exactly a place of wider coordination — think voting, demonstrations, market exchange — but certainly more public than one’s home, startup office, and marital bed. On front porches and in university corridors, on church steps and at sports games, at conferences and during opera intermissions people gather to discuss their reality. The more informedly and fearlessly they can do this, the more representative and free their government will be, being an entity charged with managing reality according to the people’s values and preferences. There in fact can be no social reality or social response to physical reality without people discussing it, and then charging an entity with its management.

In healthy democracies, most social change happens in these points of crossing. This is where we find out if a public policy is actually useful or even adopted by the real individuals who compose society, and also where whatever half-formed preference a company, a family, or a couple might come up with in private can be tested against and compared to what other people are saying and doing. Dictatorships like to absorb the semi-public spaces first. From universities to message boards, from cultural centers to benches in the park, third-space conversations go quiet, merge, disappear, and adopt new, more politically aligned tones wherever a community is not truly free to assemble and discuss what’s on its mind.

When the semi-public spaces disappear, the language of politics becomes self-contained and self-fulfilling, while the actual people retreat into their homes and businesses with their private notions that now cannot be shared in partnership or competition with the other hubs. When the hubs are so severed from one another, our collective life is over. When the hubs are so severed we start resembling the hovels of serfs paying taxes to the faraway tsar whose decisions have nothing to do with us and which we can no longer influence anyway. When the communication network of the hubs is severed, Tocqueville’s America is gone.

In my first piece in this new Substack essay series American Innocence, I wrote about how mathematical analysis of historical escalations into autocracy or other irreversible outcomes show that people, ever busy with our daily problems and preoccupations, tend to conclude too early that it’s too late and nothing can be done. When I started Interintellect in 2019, as an immigrant from illiberal Hungary and an unwilling observer of Brexit in the UK where I was living, I was driven by the definite ambition to help rebuild and maintain a semi-public space that is accessible globally, that is unsullied by partisan politics, and where people can continue to discuss what’s on their minds — ideas both public and private — come what may.

To some degree, I think my project has been successful: a case has been made for a space for challenging but friendly discussion between citizens, available at all times. We have seen hosts and attendees flourish, grow into intellectually proactive adults, academics, writers, founders, start families often with people they’ve met in Interintellect, create artistic organizations, move across the globe to live closer to each other, etc. But within my private logic, I remain dissatisfied with my own system, the one I built 2016-2019. It seems to me that there are other democratic and undemocratic forces operating under our notions of public and private. Recently, my friend Nadia looked into the matter from the point of view of how far and fast memes can spread. Atossa Araxia Abrahamian wrote about the hidden aspects of cities — the secret vaults, the exclusive clubs, the arenas blocked from pedestrian view. Last year, Musa al-Gharbi subjected New York City to the same analysis: a place of Left-talking elites and invisible service sector workers literally catering to them, another public/private division line in sense-making.

In this piece I will attempt to outline my own results so far, which in many ways differ from theirs. Please note that a lot of the things I have arrived at directly contradict my personal values or preferences, which is also why I suspect much of this is true.

I offer my investigation up for discussion here — be your comments public or private.

***

When a political system wants you to leave it alone and not cause too much trouble, you will be encouraged — through threats of violence, labyrinthine procedural language and laws nobody understands, an impotent and propagandistic media you stop believing, and abundantly available isolating entertainment that keeps you in a state of permanent brain rot — to … well … leave that political system alone.

You will suddenly decide, as if spontaneously, for your safety or for your pleasure, to return to your own household and to stay there, and to just literally mind your own business.

The moment when you do this, the political system that wanted you to do this has won. Now it no longer has to fight you, convince you, govern you. During communism in Hungary, or amid the overreaches of the Orbán regime today, people in educated, outgoing Budapest took and take it for granted that things could not be otherwise. The received wisdom is that one should let “those in power” do their thing — steal, lie, shadow-box — while normal people try to get on: the office needs new printers, the kids need new braces, there are plays and concerts to see, and the hot girl needs to be cleverly asked out so she can’t say no. When one has such little apparent effect on policy making, and when any provocation might prompt destructive reactions from those in power, why would a legally reasonable person ever get involved?

Once people are checked out this way, it is very, very hard to get checked back in again. When people are checked out, they forget the recent time when their being checked out was not the “obvious” state of things. To stay with the previous example, in Hungary, just in the late 2000s there were major demonstrations, even riots, that transformed the system of governance. Nothing about the current situation is “Lindy”, nothing is long-established and meant to stay. And even if it was, we could argue that the road to serfdom does not need to be walked down willingly.

As in my previous essay, I asked GPT 5 to use my model if it can, and elaborate:

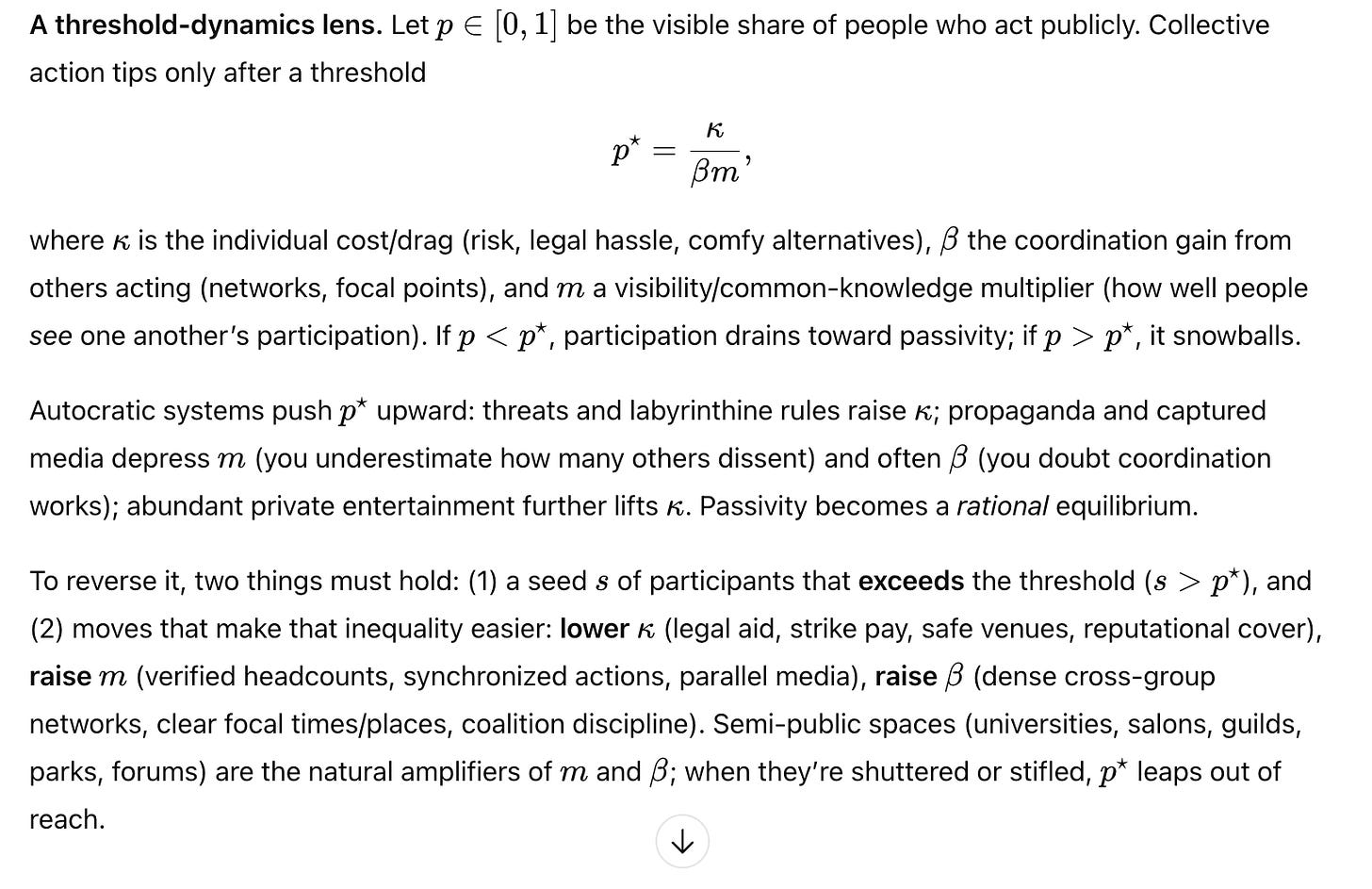

My query: “Use a formula of threshold dynamics to explain the following phenomena:

An increasingly autocratic system encourages - through threats of violence, labyrinthine procedural language and laws, an impotent and propagandistic media, and abundant available personal entertainment - the population to become politically passive, and retreat into their private lives.

If you can use this system, describe instead of this retreat what counterforce would be necessary for the threshold dynamics to reach a critical point, and the regime to realistically change:”

GPT 5’s response:

(I am aware that building on Schelling and Granovetter, Malcolm Gladwell wrote a book called The Tipping Point about this, but I have not read it. Consider also Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann’s work on the “spiral of silence”, and Timur Kuran’s “element of surprise” in collective change.)

In short, the threshold is real. When in doubt, do not “make political retreat a rational equilibrium”. Reversing something is always much harder than avoiding it.

I think Timothy Snyder is quite wrong when he suggests you just “build a private life” against tyranny — even if his counsel has value against surveillance, as a strategy for change it raises p⋆. According to the rules of threshold dynamics, the more you feel restricted by a system and want it to change, the more pressure, effort, and masses you should be producing to counter it. Getting out of the way just seems like a terrible idea that will obviously leave you with the exact opposite result to what you want. As we discussed in my first essay, your rights and equality as a participant in a society come with the duty to fight any form of collective gaslighting that wants you to think your rights and equality don’t come with this duty.

The necessity of occupying the public and semi-public spaces cannot be overstated, and no daily personal human worry can make it go away. If people only engaged in public matters when their private lives were perfect, global governance would immediately collapse!

To follow in the Straussian vein of my first post, I have been elaborating on the importance of the stable and vigorous publics because this essay is really about private life.

If you’re still here with me, then let’s go home.

Tug of War

In my 2019 manifesto which kicked off Interintellect, I expressed my belief that people = politics, therefore when you have new kinds of people you will also very soon have new kinds of politics.

My prediction has come true, but it wasn’t and isn’t without precedent. In my forty-one years so far, I have seen the rise of new types of people, and new types of politics. Pundits will praise or lament the online shenanigans of the New Left, the ascent into political power of the alt-right, but we have also seen all sorts of revanchists, transhumanists, traditionalists, effective and ineffective altruists, immortality chasers, UFO chasers, neo-religious movements — and even a handful of people who have moved to Canada for real.

Amid all this color and noise, a more drab development has also been taking place, mostly unnoticed.

Sometime during the past decades, people have become convinced that they have to make their home lives more democratic. In politics, “equality” has two distinct meanings: one means equal in value, the other means sameness. Sometime during the past decades, we decided that our backstage lives — the lives we spend in private — must start including more sameness than previously.

It is natural that people would be confused by the fact that working democracies consist of deeply undemocratic hubs. The thing is a happy family, a well-oiled cohabitation of housemates, two people in love, or a successful startup are very far from being “democratic” or “based on sameness”. Authority and decision-making, exciting personality differences, chains of provisioning and care hold these hubs idiosyncratically together. In some sense, none of these hubs should even work. But they do! That is why to an outside observer, what makes somebody want to work at a specific company or why a couple are attracted to each other can be so baffling and incomprehensible.

No one gets it because it should not in fact “make sense” in the political sense. Take a family for example: in a multigenerational household most people (the elders, the children) don’t earn money at all (are in school, are retired), many don’t vote (under 18), and trying to extend the sameness to all participants (send the grandparents and kids to work?) would be inhumane if not insane. At a startup, co-op style collective representation would be the end of brand, speed and revenue. In a couple, sameness and the accompanying legibility would kill the very myths that draw the two people together. So if you don’t understand why in a family of six that includes two earners, and a genius teen in college, it is still tiny, frail, ninety-year-old Grandma who has never worked a day in her life whose word is ultimately decisive in any matter of dispute, it’s because you’re not supposed to. It is private. Private life is not supposed to be “democratic”. Our democratic systems are built of undemocratic hubs — little personal monarchies — and that is perfectly OK.

Except the world today is conflicted about whether this is OK. Watching my Millennial friends get married and have children, I’m seeing experiments ending in variable results of creating households of absolute equality. What on paper seems desired, because it is desired in public life, namely a bureaucratic equality in the home, seems to be a complex blessing even in best case scenarios. I’m seeing a lot of work, a lot of fighting “natural instincts”, a lot of diminished efficiency, a lot of pushing back against what makes people interested in each other. What is gained, of course, is a kind of democratic dignity, dignity as a public ideal. It is less politically correct these days to ask whether “dignity” is the same inside the small hubs that work best when quite undemocratic as it is out in the public square. You notice this right away when you try to force the moment to its crisis and take some of the current governing ideas to their extremes: Would children have more dignity if they could run for office? Does a startup freelancer’s dignity really increase if they can veto a CFO’s decision? (Did women really have better sex during socialism? Not based on anything I’ve heard!)

You might — often correctly — think: well, OK. So we pay with some lost efficiency for more dignity and representation within our little hubs (companies, families, couples). Don’t we already make these compromises in the public and they’re called “liberal democracy”? We enter social contracts and swear allegiance to collective deliberation, even if some theories suggest a king or autocrat would make faster decisions. In fact, we have discovered that collectively we are smarter and can consider more aspects of reality, therefore decisions that come out of deliberation instead of dictatorial whim will be better decisions. Nothing about liberal democracy is “natural”; we had to learn to live this way and wait for longterm results to conclude this is the best arrangement available however imperfect. So it would make sense to think that after establishing this liberal arrangement outside, it was time to “bring the reforms home”. To now start cleaning out all inequalities, all shortcomings in the little hubs where individuals spend most of their time: their workplaces, their clubs, and their households (all of which after the pandemic are so often the same place).

There is a counterintuitive problem with this, however. The outcome is undeniably visible. When given the choice, people do not seem to want to live in a kind of Phalanstery (truly egalitarian home setups from religious fundamentalists to socialist kibbutzim have been self-contained or temporary).

Sameness also means competition in the Girardian sense — too much competition inside a hub weakens the hub as a player in wider society. When families are in constant dispute, the compulsion might arise to try to solve the matter through public ideology and seek powerful leaders who tell you that yes, you are right and your mom is wrong.

The more egalitarian our private lives are becoming, the more we are seeking dictatorial arrangements in public life. Today, men and women throughout the West congratulate themselves on taking turns at taking out the trash, and then go online and celebrate the breakdown of Western democracy.

The results are the opposite of what you want: less individual color and abandon in the home, and more uniform autocracy in public — a uniform autocracy which step by step erodes the very values of individual equality for which we started reforming our homes and hubs in the first place.

Make It Make Less Sense

In Tyranny as Tragedy, we concluded none of this has to be so. None of this is “fated”, past the tipping point, or arising from some ironclad logic irreversibly. Not yet.

A great way of avoiding the collapse of civic life is to make your home life a little crazier. Or, if it happens to be crazy by default, then just to leave it so.

Intellectual and biological families are self-expression. A democratic public is an expression of collective will. Reversing these two things will lead to the opposite political result of what we want.

There are many benefits to letting the undemocratic hubs from which liberal democracies are built remain themselves.

(1)

The social contracts that bind our personal hubs together are based on personal choice and emotional closeness: a calling to join a group, the act of falling in love, the attachment felt toward relatives are almost always stronger than whatever “unfairness” a person we feel we belong to might commit against us.

Our social contract with the public is far less elective — in the rare cases where we truly can’t live with the form of government we are subjected to, we either have to successfully rise up against it (hard) or leave (hurts). Because of this high price and threshold, having a rational and public say in public matters is crucial.

Private “contracts” are and should be much more complicated. Here, leaving is often far easier and just how people wish to govern themselves can and should be flexibly negotiated. In some cases, a family or company might decide to run themselves fully democratically, but most often they will not, and that is fine. We should point out that the whole point of love is to complicate all social contracts: what could be transactional isn’t, what should be fair is often not, and people seem to take pleasure in carving out a space in their lives where common sense does not need to rule: we give the other person a chance to be a little crazy and in exchange they also give us this same chance. Everybody wins (and recharges).

(2)

Let’s assume that all people are some combination of rational and irrational agent. Even if on the whole the world is becoming a more reasonable and peaceful place, since these are relative qualities, some parts of life, some actions, will necessarily remain more irrational than others. One way of dealing with this would be to ensure all arenas are built mostly on rationality but have some irrational element left in them, a kind of pressure vault.

Another way of going about it would be to help create — or leave intact — entire arenas dedicated to or tolerant of irrationality. For example: Should artists be allowed to be politically incorrect? Can lovers be allowed to be unfair?

Life is not a single homogeneous system, more like an economy: rational and irrational must balance. From where I’m looking at it, attempts to make the private sector and the private life, where things like existential competition and competition for parental attention; romantic love, sex, and death; childbirth, cultural succession, and rebellion; financial worries, creative innovation, and self-narrativization; spiritual beliefs, altruism, and emotional consolation take place to be “more reasonable” seems completely unreasonable if not ridiculous. If there is any realm in life that we might want to keep irrational, the rational thing is to make that the private life.

Keep your love life suffused with symbols and struggle, your company verging on a religious cult, your roommate situation one where you can kick somebody out “based on vibes” all you want — just please don’t bring these urges into politics.

(3)

But this is exactly what is happening. As home life equalizes and bureaucratizes, our despotic instincts are pushed out into the public. Multiple bad loops begin. On the one hand, chaotic (lack of) decision-making seems to make populations crave more decisive, more dictatorial leaders on the public stage. (A famous artistic depiction: Sławomir Mrożek’s excellent play Tango. Here the unreliable, “democratic”, bohemian, Boomer-like parents spawn sectarian, paramilitary offspring. Sounds familiar?)

On the other hand, illiberal leaders will cater to the population’s dissatisfaction in their customary populist way, and so new, “edgy” slogans will pop up, for example to remove women from higher education as a way of “solving” the men’s college admission and alleviating the fertility crisis, or to block talented immigrants from coming into the country to work at startups because that is “unfair” to the locals.

This regression is not what we mean by “letting the hubs be their natural selves” — there is nothing natural about uniform oppression. It’s much more like: unless you ensure your own household can be its own kind of crazy, the wider public will go crazy and impose that very uniform craziness on your hub too, until you check out and disassociate.

(4)

Democracy is not just about self-representation. Individuals in any liberal democracy also represent their households, their oikos. Allowing your artistic guild, your extended family, your polycule, your community garden, or your web development agency to be what it organically wants to be, even if that is not per se democratic, will make the people in it more passionate participants in democracy. Now you are representing not just yourself but all that you love in the world.

***

Due to certain gaps in my general education, I have only recently come across Arrow’s impossibility theorem which is also one of the reasons why I decided to finally write about this topic.

Arrow’s theorem states that when a group has more than 3 options, it will be impossible not to break one of the four pillars of fairness…

Unrestricted domain: The rule must handle any mix of people’s preferences

Non-dictatorship: There isn’t a permanent boss whose ranking always becomes the group’s choice

Pareto efficiency: If everyone prefers A over B, the group should also prefer A over B

Independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA): The group’s decision between A and B should depend only on how people rank A vs B, not on a third option C

According to Arrow’s theorem, the fact that one of these axioms will have to be violated where there are 3+ options to choose from and so some unfairness will necessarily be committed is mitigated by a “layering” in democratic decision-making: primaries, coalitions, Supreme Court, etc.

In my understanding, Arrow’s theorem proves that it is quite impossible to make smaller hubs fair in the democratic sense. Layering seems to be impossible in small-number groups, be it a marriage, a creative co-op, or a laboratory. You will just have to be unfair along one of these lines — and, once again, that is fine.

I asked GPT 5 to try and apply Arrow’s theorem on my little theory:

Family: museum vs beach vs football

Suppose the three of you rank Saturday plans like this:

Parent: Museum ≻ Beach ≻ Football

Teen: Beach ≻ Football ≻ Museum

Child: Football ≻ Museum ≻ Beach

Pairwise votes produce a cycle:

Museum beats Beach (2–1),

Beach beats Football (2–1),

Football beats Museum (2–1).

No stable winner! To move, families quietly drop an axiom:

Non-dictatorship breaks: “Okay, Mom decides this time—Museum.”

IIA breaks (context flips A vs B): “It’s going to rain, so Beach is out—Football vs Museum now feels different.”

Unrestricted domain narrows: “No football in crowded parks—choose Museum or Beach.”

Or you smooth “fairness” over time (rotate who chooses; split domains: “you pick Saturdays, I pick movies”).

Startup: which feature to build first

Three founders rank options:

A: Payments ≻ Dashboard ≻ Notifications

B: Dashboard ≻ Notifications ≻ Payments

C: Notifications ≻ Payments ≻ Dashboard

You can again get cycles. To ship, teams pick a poison:

Designate a product owner (relax non-dictatorship): “PM makes the call—Payments.”

Let context reweight choices (violate IIA): “Big customer needs Payments → that flips Dashboard vs Payments.”

Restrict the domain (limit unrestricted domain): “Only features with revenue impact count this quarter.”

Bottom line: Families and startups work by explicitly or tacitly relaxing a fairness axiom—using roles, context, or time-sharing—because perfect procedural democracy with 3+ options is logically impossible and practically paralyzing.

This, of course, raises deeper epistemological questions about what “rationality” even is. You should be reading these real-life examples and feeling that rational does not equal fair: Mom is being perfectly rational in her choice, and so is the PM. It is simply that in the public realm what is rational and what is fair just works differently. One could argue that the Wild West that is every family, every couple, every group of inventors is closer to the baseline human rationality. Theirs just is a type of rationality that we call “crazy” — and a type that works best when confined to smaller hubs, so the doctrine of fairness doesn’t end up being accidentally relaxed for the entire country.

***

Philosophers have of course been on to this for a long time. To Aristotle, the oikos was a monarchy. Hegel thought the family was ruled not by rights but by love (in fact that rights begin only when the family dissolves). Flaubert wanted you to be a well-respected citizen, so you can taste excess in private. If you’re American, the above might have reminded you of Oakeshott’s ideas of “enterprise associations”. If you are like me a European, you must be smirking now remembering the Dionysian madness in Nietzsche, and the irrepressible necessity of keeping it alive in certain parts of the self and society. You will also recall Kierkegaard’s loving and unfair God breaking His pact with Abraham and then renewing it even stronger, or how to Kierkegaard personal commitment was aesthetic self-expression.

If you look closely enough, the theme pops up all over the place: the art nouveau pornographer Georges Bataille of course wanted you to have an unproductive realm in your life. Max Weber warned you against dried-out Protestant ergonomics. The Frankfurt School warned you against a loss of identity.

Even Hannah Arendt — so unfairly in love herself — contended that freedoms might just be the stuff of public life and nowhere else. Just as I was fact-checking this essay, I ran across a few sections in her The Human Condition which I had only read in parts until now.

Here is a GPT 5 summary of these parts of the text:

In The Human Condition II, Arendt draws a strict boundary: the household (oikos) is “born of necessity,” a sphere of unequal, life-maintenance labor, while the polis is “the sphere of freedom,” where equals appear to one another in speech and deed and where “what is merely necessary or useful” is excluded from politics; modernity dissolves this line in the “rise of society,” the pulling of “household and housekeeping activities to the public realm,” so that public life becomes enlarged housekeeping and private life thins out. Within this map, love has a definite place: “love, by its very nature, is unworldly,” indeed “not only apolitical but antipolitical”; it needs shelter from publicity, just as politics needs protection from domestic necessity. When we blur the realms, both suffer: action and plurality decay in public, and the thick, intimate affections of private life are distorted or evaporate.

It is quite interesting that a lot of monarchic impulses in contemporary American politics (Thiel, Yarvin, crowned Trump memes on X) come out of the success of such arrangements in the private realm of startups. Trying to apply kingly instincts on the wider public has led to mixed results.

My startup, Interintellect, is definitely not a democracy. But my undemocratic hub, in the larger sense, does contribute to the American democratic system. We produce goods and make money, employ people and pay taxes, and through our successes make American business more competitive on the international scale. By being weird, efficient, innovative, and unique, our mere existence increases creative pluralism in the United States. And so it is with every hub — companies, families, orchestras, love affairs — in any free country where expression is allowed and the state doesn’t interfere in the private sphere of individuals.

Our battles for equality should be fought in public; making the home the main “domain of the fight” in the Marxist sense is ill-conceived. While you were so focused on who empties the dishwasher or whether playing Pictionary at the team retreat would offend any one of your 150 employees, far bigger and more ominous versions of unfairness have entered the public realm and now will be very hard to get rid of.

***

I have been musing about these seemingly paradoxical phenomena ever since I moved to the US last year. Oftentimes you really have to see things up-close to gain an understanding. It is because the theory sounds so contradictory that you have to see how life, in its infinite and insane wisdom, allows for the irreconcilable to coexist and create ultimately positive processes.

I must admit that I had resisted my own intuitions about this for quite a while, and that is very typical of how full of biases and prejudices we all are facing universal facts thanks to whatever particular life experience we might have undergone. I grew up in an extraordinarily chaotic family myself where both of my parents worked — first successfully, then unsuccessfully — in show business. Rules were arbitrary, homes were loud, and I was often afraid for my safety. Sexual mores were exploitative: babysitters were harassed and then disappeared, girlfriends were discardable. Crime was always at the doorstep (ask any film producer what I mean by this). Up to relatively recently, my personal, self-defensive instincts always revolved around “making my home quieter and more rational”, because in my mind chaos equaled the very unique and strange circumstances I experienced in childhood. Now I know that I was somewhat wrong. There is healthy crazy. My company is healthy crazy and has been for many years. My long, deep, passionate friendships and loves are all healthy crazy. They contain no sameness and little democracy, but all rest on respect and dignity for equal value. Perhaps that is what religions call “grace”. Perhaps there is only a religious way of even conceptualizing it.

These days I think “grace” just manifests very differently in public and in private — and this difference is softened and diluted in the semi-public spaces the survival of which we must all fight for with all our resources. Make the home grayer and less fun, and people will bring their need for transgression out into the open, into the public where close and tactile bonds and irrational love cannot overwrite the gross unfairness. The grace of the publics, as Habermas thinks, is discursive and rational. But every home is a home of the animal. Let the animal out of its natural dwelling place and it will wreak havoc where laws should be made.

Turn your ambitions outward and bring your world-changing to the public. The dishes can wait. By letting your home be a little messier, you will end up creating a public that is more perfect.

Have you ever seen the movie Together? It’s a Swedish movie set in a 70s polyamorous commune. It’s a utopian attempt to live at home as they believe the world should be, but human nature intrudes.

“As home life equalizes and bureaucratizes, our despotic instincts are pushed out into the public. Multiple bad loops begin. On the one hand, chaotic (lack of) decision-making seems to make populations crave more decisive, more dictatorial leaders on the public stage.” Yes that’s quite true. It’s also making me think of the wider bureaucracy of life in recent years and the overwhelm of admin. Dictatorial leaders cut through the noise of the attention economy, the drastic moves they make signals the sign of getting things done — not that these things getting done are necessarily great for the majority. Really interesting read.