Tyranny as Tragedy

I'm starting a new blog.

Hello friends! I’ve finally got the “American Innocence” domain, and so I am starting the blog I’ve been meaning to for a while, about my new life in America. Expect a wide assortment of various ideas that I’ve been musing about, being newly based in New York and traveling around this fascinating country a lot. As always, I’m super excited for your comments and suggestions below. My old “Eleven Sentence Essays” will remain available, but I’m moving on to a longer format for the time being. Thanks for reading!

Anna

Tyranny as Tragedy

“The most important rule of theater is that the king is never played by the actor playing the king, but by all the other actors around him.” (Old theater adage)

The greatest playwrights know everything about human nature not because they have some mystical, clairvoyant insight into you or me, but due to the structural constraints of their format: in order for tragedies to work — for problems, decisions, and plot twists to be accepted by the audience as true — the writers must learn to tweak the interactions between the characters until those seem logical and believable to all. Accessing good theater gives you a significant cheat code for accessing human thinking and behavior. Read Sophocles, watch Laurence Olivier’s Shakespeare adaptations, see Molière or Chekhov on stage, enter a book club debate about Brecht, David Mamet or Yasmina Reza, and you will experience many “Aha!” moments that will be assets in your subsequent life. You will also, of course, feel aesthetic pleasure and what Aristotle calls catharsis, or emotional purification, which is why most people engage with plays in the first place. The great knowledge that you will be gifted is just the bonus.

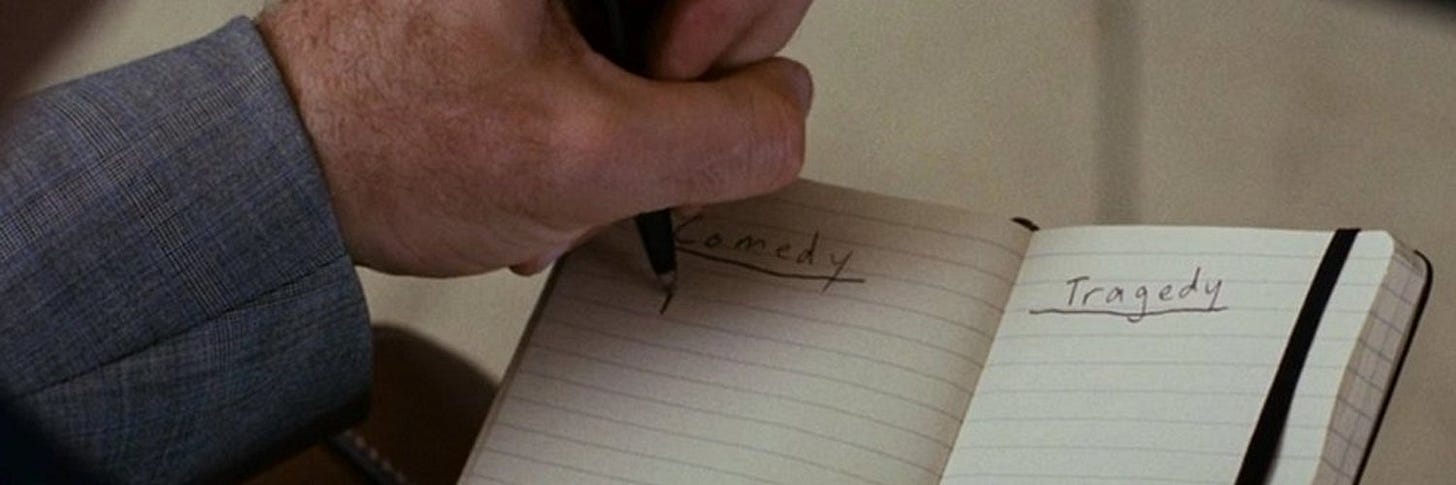

How dramatic storytelling works — to paraphrase one of my favorite movies on the matter, Stranger Than Fiction — is simply: “in comedy you get hitched; in tragedy you die”. This is a fun way to summarize how theater always deals with love and death, nothing less. In the comedy Much Ado About Nothing (spoiler!) of course the sparring man and woman eventually fall in love and marry, and we can assume they will go and make many babies. (“The world must be peopled,” says Benedick.) Life. In the tragedy Hamlet, the last scene leaves the stage covered in corpses (some people even die behind curtains or while being shipped to England). Both would-be fiancé and fiancée perish, a foreign power takes over the nation, and there are definitely 0 babies. Death. We like to criticize the kiss at the end of canonical Disney films, but they are not as superficial as you might think. The other option is extinction.

The most infuriating thing about tragedies is that they are avoidable. Oedipus could technically marry someone completely different who is not his own mother. Sure, the prophecies tell him he will do this, but it is then his own free choice to see the nuptials through with a total stranger. (Then, of course: Surprise!) All blockbuster movies about disasters emphasize human error and not just because we humans think we’re the center of the universe (although we do). Delayed evacuations in invasion movies like Independence Day cause many people’s death, greedy humans fake coroner’s reports and don’t shut down the beaches in time in Jaws, human hubris and business interests allow for the T. rex to break free in Jurassic Park, and elitism and incompetence create unprecedented loss of life on the Titanic. It is because these events would be avoidable or at least mitigable that we feel these stories are tragedies. A tragedy is always human doing. (Contrast this with movie plots like the terminal illness in Terms of Endearment that is nobody’s fault or, e.g., The Impossible where a family’s members all miraculously survive the Thai tsunami. Watching the movie, the 2004 tsunami may be registered in the viewer’s mind as one of the saddest events in recent memory, but we experience it as drama, not tragedy. No one is sinning; in fact the characters are doing the best they can and more.)

Humans make bad decisions in comedies too — every comedy is a “comedy of errors”. These errors tend to revolve around some deception that propels the characters to change and grow until the mistake is revealed and cleared up. In a farce, characters run around and hide behind doors to eavesdrop on a secret rendezvous. There is a lot of cross-dressing in comedies from Shakespeare to Some Like It Hot or Tootsie, everybody falls in love with the wrong person and then somehow all’s well that ends well. We love to laugh at stupidity the way it is represented in comedy because we can feel smarter than the deceived characters. In tragedy, stupidity is death, and the audience is overpowered by the feeling that they can see the evil outcome coming but can do nothing to stop it. The Shakespearean Prologue — starting the play with the spoiler — is a fine proof of this. The Three Witches who curse Macbeth in their opening dialogue resign us to the horrors we’re about to witness without giving us any concrete pointers. That Richard III tells us at the beginning that he plans to become a murderous jerk offers us scant comfort when we’re helplessly watching him execute (quite literally) on his promise. In a comedy, we’re usually aware of the truth right away and laugh our way along until the characters catch up to it too. In a tragedy, truth and method build up gradually, inescapably, and the fact that we’re aware only increases our own sense of impotence. We’re spiraling along with the characters. While a comedy might help us escape from real life, tragedy feels too much like it, and our only hope left is Aristotle’s empathetic purge: in his framework, humans become better people when seeing a tragic play and I believe that is correct. Facing what feels structurally inevitable, the only reaction we have left is emotional.

Every tragedy is a study of escalation. After each event, each scene, fewer options remain to avoid a bad outcome. Let’s take a popular example I’m sure you’re familiar with: Romeo and Juliet.

When the play opens, we are told what will happen: two young people from rival families will meet, fall in love, and then die. (Remember: tragedy = death = no babies.) But when the play opens, we see no problem: Romeo and Juliet don’t know each other, Romeo is pining for some other girl, and only his emo friend is talking about the dangers of love. At this point, anything can still happen — and be avoided.

Then the escalation begins. In each scene, the characters start making decisions that leave fewer choices in the next, until the only option that remains is death. With each new event we will forget the previous scene where none of this seemed predetermined. After each scene we will be more and more convinced that the horrible development of events is the correct, logical, predetermined one. I’ve always wondered if in Shakespeare’s time the Prologue was really a heads-up to the audience before the play so they don’t end up storming the stage later and trying to confiscate the actors’ daggers. (“FYI, guys…”)

In her first scene, Juliet learns she’s now an old lady at 13, and will very soon be expected to marry and sleep with some old guy she hasn’t even met. In that moment, she kind of grows up: now the idea of hooking up with a man is suddenly not so ludicrous to her. Romeo crashes a party to stalk his crush. He instead falls for the first rebound he encounters, the newly maturing Juliet. A lot of things that a few minutes ago felt unthinkable, now make “total sense” to the audience. Of course this happened! We heard that they were consciously or subconsciously looking for love anyway! And then they ran into each other! Of course! The audience can nod or shake their heads knowingly.

Romeo, having just entered puberty himself, will of course sneak into Juliet’s garden at night, and then somehow end up proposing to her. She is of course more psyched about the idea of marrying into her own age group if she can choose. And it is because she can choose that the escalation continues…

Whether in a tragedy or comedy, when people marry (Romeo and Juliet) or die (Mercutio, Tybalt) the options suddenly narrow very drastically. Just like in real life! In this play, exile, missed messages, pretend-poison and real poison are now at play. Romeo runs into accidental, external obstacles — the Capulet boys looking for a fight, Balthasar arriving too early — and must react. Juliet encounters internal restrictions. In one of the most brilliant scenes in the play, Juliet’s nurse gives her the option to betray Romeo and just chill out and go double-marry her original suitor, but by this point Juliet is of course not free to make this choice, both out of love for her new husband Romeo and because of law and religion. It is simply no longer possible. Each scene tightens on the previous scene’s noose around freedom. And so even before risking real death, Juliet must choose a death of her identity: losing her hometown and following Romeo into exile, and losing the one person who is like family to her, the Nurse, whom she loved and trusted her whole life (and who assisted with and encouraged her affair with Romeo). If you thought this play was only about young lust and bad luck, ask yourself if you, the adult, would behave as honorably in such situations as do these two Verona kids.

If you like mathematical explanations, you can model a tragedy as an entropy funnel:

Every scene in Romeo and Juliet adds constraints that eliminate alternatives and raise the probability of tragedy: the surprisal (−log p) of that ending steadily falls.

Bigger shocks like the life/death events we mentioned above are high-information pivots that fast reduce the option space and reconfigure the transition graph. Formally, the story is an absorbing Markov chain with BOTH DIE as the absorbing state and fewer and fewer return edges to safety.

Because the Prologue reveals the outcome, audience outcome surprisal is near 0 from the start. Instead we’re dealing with path surprisal: the high-information question of how the (sense of) inevitability is reached.

When we watch The Impossible, we mourn those who died because of the tsunami. Watching Romeo and Juliet we mourn ourselves: we saw the escalation, we saw the window of action narrowing, we knew those decisions were steadily decreasing the likelihood of a good outcome, and we just watched along and felt more and more that there was never a way out anyway. We’re left with the vague and disturbing memory that none of this should have happened. That Friar Laurence should have just briefed Balthasar, or Romeo should have just got Tybalt arrested instead of killing him, and that the two lovers should have somehow either reconciled their families with the help of the Prince or gone into exile together and had all those babies people in comedies have. (But then Romeo and Juliet would have been a comedy. At the end of Much Ado About Nothing, the similarly fake-dead Hero is “resurrected” and she does marry Claudio and have the babies, etc. The fact that in comedies things turn out well and in tragedies they don’t, despite the very similar topics and storylines, reminds the audience of the immense, almost unbearable fragility of life: we all live on the knife’s edge between comedy and tragedy.)

In comedy, you laugh because the characters should know better. In tragedy, you mourn because you should have known better.

***

Some famous tragedies — Antigone, Julius Caesar — are about tyrants. But every tyranny in real life works like a tragedy. Every tyranny is a study of escalation. Tragedy is about death, and comedy is about life. Maybe this is why autocrats hate comedians so much.

Autocracy is the death of freedom, and how societies get there is by a process of escalation after every step of which people feel they have fewer choices, and the outcome feels more and more inevitable. Step by step people forget they used to have more freedoms just a minute ago.

The Canadian war historian Margaret MacMillan jokes that there are 15,000 books written about why the First World War broke out — because we don’t understand! (There are 0 books written about why the Second World War broke out because that we do understand.) How the European powers at the start of the 20th century talked themselves and each other into the all-transforming carnage that was WWI still requires accurate scholarship to even begin to understand: it was entirely avoidable, and only felt mysteriously “fated” to those locked into the step-by-step machinery of conflict escalation at the time. The result, as you know, was tragedy. Destruction at a previously unimaginable scale that changed our economy, mindset, and society forever. Our world today is still as WWI left it. And 15,000 books still cannot figure out why the whole thing happened; why people — people just like you and me — chose to make it happen.

How societies lose their freedom to tyrants follows the same pattern. There is a reason why so many autocrats come into power in wartime or during some perceived threat. Carl Schmitt (pro) and Giorgio Agamben (con) will tell you about the dubious terrains of a state of exception. Roman history will show you that some dictators (Cincinnatus, Sulla) leave after the danger is over — but that many don’t or don’t want to. Contemporary theorists like Richard Sennett or George Lakoff will outline, in a kind of Hegelian master/slave setup, how authoritarians can stay in power largely because they relax us with their fatherly presence. We feel safer and we don’t want it to end. We give up our autonomy when manipulated into it, in exchange for what we see as attention and care given to us. Anne Applebaum and Johannes Gerschewski explain the importance of co-option in the consolidation of power: successful, lasting tyrannies make sure that mediocre apparatchiks, minions, heads of satellite states, etc., get more power in the unfree, centralized arrangement than they would in a more competitive, open system where they would just be total losers probably.

Underneath all these helpful theories lurks the question of escalation, and the reaching of the point from where there is either no return or at least people feel there isn’t. (When it comes to outcomes, the two are sadly the same.)

Let’s think about the Roman Empire for a second. The rise of the democratic Octavian into the autocratic Augustus was entirely avoidable for a long time. Many, many steps had to be taken from which things could still have gone another way, or been undone.

To ensure my analysis is accurate, I’ve enlisted GPT 5 to follow my Romeo and Juliet entropy funnel model and apply it on the rise of Augustus as an illustration of how options narrow “as in tragedy, as in tyranny” (I have reformatted it slightly for your ease of reading):

Octavian’s rise is an entropy funnel toward the absorbing state ONE-MAN RULE: early off-ramps exist but shrink quickly.

44 BCE (Caesar’s will/adoption) concentrates name, cash, and veteran loyalty—avoidable if the Senate had contested the testament or Octavian stayed a private heir (p ≈ 0.25; avoidability: high).

43 (Lex Titia, Second Triumvirate) suspends normal politics—avoidable if powers were refused or tightly time-boxed (p ≈ 0.40; avoidability: medium).

42 (Philippi) destroys the main republican armies—avoidable if Brutus/Cassius won or forced amnesty and a constitutional deal (p ≈ 0.60; avoidability: falling).

41–40 (Perusine) secures Italy and land for veterans—avoidable if land reform compromised or L. Antonius/Fulvia prevailed (p ≈ 0.66; avoidability: low).

40–39 (Brundisium/Misenum) buys time and grain while Agrippa builds a fleet—avoidable if Sextus’s blockade compelled a Senate-led peace capping all three men (p ≈ 0.68; avoidability: low).

36 (Naulochus + Lepidus sidelined) leaves Octavian master of the West—avoidable only if Agrippa lost at sea or Lepidus remained coequal (p ≈ 0.82; avoidability: minimal).

34 (Donations of Alexandria) hands Octavian propaganda—avoidable if Antony kept Roman optics (p ≈ 0.84; avoidability: minimal).

32 (Antony’s will exposed; war on Cleopatra) nationalizes the conflict—avoidable if the will stayed sealed and arbitration replaced a “foreign” war (p ≈ 0.89; avoidability: minimal).

31 (Actium) breaks Antony—avoidable if he fought on land, escaped with the fleet, or accepted partition (p ≈ 0.94; avoidability: vanishing).

30 (fall of Alexandria; Egypt annexed) yields treasure, grain, no peers—avoidable if Egypt became a senatorial province or its revenues were put under public control (p ≈ 0.96; avoidability: vanishing).

29 (triple triumph; Janus closed) normalizes a peace mandate—avoidable if honors were tied to term-limited emergency power (p ≈ 0.97; avoidability: vanishing).

27 (First Settlement) “returns” power while keeping the legion-rich provinces—avoidable if the Senate retained those provinces/legions under rotating commanders (p ≈ 0.985; avoidability: near-zero).

23 (Second Settlement) adds tribunicia potestas and imperium maius—by now practically inescapable, avoidable only if the Senate denied or strictly time-boxed them or required a permanent coequal with veto (p ≈ 0.995; avoidability: negligible).

My view: after Naulochus and Lepidus’s removal the option space collapses from “reversible with luck” to “structurally locked”—resource control, veteran patronage, and the 27/23 constitutional toolkit erase return edges, so p(Principate) → 1, and “avoidability” becomes mostly counterfactual embroidery rather than plausible politics.

(I like it when ChatGPT says “my view”…)

As the kids would say about the above: many such cases. When people start feeling that there is “no other choice”, [1] that is almost always the result of our own previous actions, and [2] there is almost always a lot more other options left than we think (yes, even 1 is a lot more than 0!).

In fact, we tend to start thinking there is “no other choice” way too early: the mathematical analysis of both historical tyrannies and famous tragedies show just how many things could still have been done. Tyrannies — like tragedies — act like self-fulfilling prophecies if one is not careful. (No wonder the Greeks actually put self-fulfilling prophecies into their plays, see the aforementioned Oedipus Rex.)

If you read the go-to works of political philosophy such as Carl Schmitt or Michel Foucault, you will notice descriptions of — even advice around — escalation or avoidance thereof. I like to joke that Schmitt, while purportedly on the Right of course, could totally be read from the Left as a manual for avoiding being subjected to dictatorship. You can literally go read what an autocrat would want to do to you and just not allow it. It’s right there on the page, openly.

On the other side, Foucault, our celeb lefty, can be easily read by an enterprising right-winger as a manual for imposing total surveillance and loss of identity on a selected populace. You can organize a book club (list it on Interintellect?) where you go through the two books chapter by chapter only focusing on escalation (of loss of freedom) and evitability (counteraction options).

We humans seem to be uniquely bad at discussing or even perceiving our options. As in our personal lives, we’re blinded by our conflicting emotions — and life is not an airplane where exit routes are marked on the floor by twinkling arrows. Egyptians who remember the 20th century, people who were in Russia or Turkey in the past 25 years, will tell you how they noticed they had lost their freedom “too late”. They will, quite wrongly, conclude that by the time they became conscious of violence, censorship, the disappearance of the opposition and their funding, how the media turned into a propaganda factory, how the leaders’ imaginary enemies started populating the discourse, the official marginalization of certain groups in society, how parliamentary deliberation had become a parody of itself — or how in some cases even an outright war could suddenly break out — there was already nothing they could have done. That somehow a handful of people in suits was stronger than an entire nation, and that the money, talents, and intelligence of millions or hundreds of millions of people were somehow not enough to find a different way of doing things and build it.

When it comes to classical dictatorships, at some point the people would be almost right: after a while, indeed, there was nothing left to do, or at least almost nothing — just like for Romeo and Juliet. In modern illiberal societies, however, this is rarely so final. I’m originally from Budapest and I was there watching the rise of Viktor Orbán in front of my face from his 2002 election loss until the consolidation of his power in 2012. All of it was entirely avoidable. And Hungary still isn’t a military dictatorship with a violent secret service like, e.g., Stalin’s USSR was. All of it is happening in broad daylight in the middle of Europe and, sure, things might be difficult to change but it’s not like nothing can be done.

Here is GPT 5 again — I’m using it for accuracy (dates, names, etc.). I’ve asked it to apply my tragedy model (my “tragedy as entropy funnel” idea) first on the consolidation of dictatorship in Egypt:

Think of modern Egypt’s 20th-century authoritarianism as an entropy funnel whose absorbing state is a military-presidential security state: each pivot shrinks the republican/pluralist option space and lowers the surprisal of one-man rule. Egypt (absorbing state: military-presidential security state). Modern Egypt’s consolidation is an entropy funnel in which early off-ramps narrow fast and p(autocracy) climbs.

1952–54 the Free Officers abolish parties, sideline Naguib, and crush the Brotherhood after the 1954 attempt on Nasser—avoidable if parties had remained legal and a dual-power arrangement survived (p ≈ 0.35 → 0.45; avoidability: medium).

1956 a plebiscite constitution installs Nasser and a one-party mobilization machine; Suez furnishes a legitimacy windfall—avoidable if multiparty competition had been preserved and plebiscitary politics resisted (p ≈ 0.55; avoidability: medium).

1962–66 the National Charter founds the Arab Socialist Union as sole party and Qutb’s execution signals ideological repression—avoidable if single-party monopoly and political trials were rejected (p ≈ 0.65; avoidability: falling).

1967→ the Six-Day War ushers in routine Emergency Law, normalizing exceptional courts and detention—avoidable if emergency powers were tightly time-boxed and judicially constrained (p ≈ 0.75; avoidability: low).

1971–81 Sadat’s constitution hard-wires a very strong presidency; the NDP (from 1978) converts “multi-party” life into de facto single-party dominance; after Sadat’s assassination, Mubarak keeps the emergency for decades—avoidable if executive/emergency authorities were pared back and party dominance not fused with security rule (p ≈ 0.90 → 0.95; avoidability: minimal).

Arab Spring and today: 2011 topples Mubarak and briefly widens the option space; 2012 elects Morsi; 2013 the military ousts him and the ensuing crackdown re-closes the system; 2014–19 constitutional/institutional changes entrench the presidency; 2020s elections under Sisi restore the pre-2011 trajectory—net effect: avoidability spikes briefly in 2011–12 then collapses again, with p(autocracy) returning toward 0.95–0.98.

On the other hand, if I ask GPT 5 to run the same model on how “inevitable” the irreversible-looking entrenchment of the power of Viktor Orbán — or, in fact, of any potential illiberal leader in the West — is, things look much less stark. It looks like, mathematically, we in the West are indeed far more free to take action against the ossification of autocratic systems, and to avoid the reaching of points that will feel like points of no return.

In short, in the West (and that is not an accident but by design a part of our political systems) we can — with more or less effort — avoid and/or reverse processes of dictatorial escalation.

Hungary / Orbán (absorbing state: DOMINANT-PARTY RULE). Orbán’s trajectory raises p(autocracy) but stops short of full absorption because EU/legal counterweights persist.

2006–09 setup: the leaked Őszöd speech and riots discredit incumbents; the 2008–09 crisis and a technocratic interlude prime voters for a reset—avoidable if the governing camp had stabilized earlier and shared reform ownership (p increases modestly; avoidability: high).

2010 Fidesz–KDNP wins a two-thirds supermajority—avoidable if supermajority use had been self-limited by cross-party pact (p ≈ 0.35; avoidability: medium).

2010–11 media laws create a powerful regulator—avoidable if appointments were plural and review robust (p ≈ 0.45; avoidability: medium).

2011 the Fundamental Law plus many “cardinal” laws entrench two-thirds constraints—avoidable if domains were narrower, sunsetted, and opposition-backed (p ≈ 0.60; avoidability: falling).

2011–12 electoral redesign (single-round SMDs, redistricting, “winner-compensation”) structurally tilts competition—avoidable if an independent map and two-round or preferential voting remained (p ≈ 0.68; avoidability: low).

2013 the Fourth Amendment narrows Constitutional Court review—avoidable if rule-of-law recommendations were heeded (p ≈ 0.72; avoidability: low).

2017–20 “Lex CEU” squeezes a flagship university (later found incompatible at EU level)—avoidable if higher-ed rules complied with treaty obligations (p ≈ 0.76; avoidability: low).

2020 a pandemic enabling act normalizes ruling by decree—avoidable if strict time-limits and oversight applied (p ≈ 0.80; avoidability: low).

2021 public-interest foundations move assets and universities to loyal boards—avoidable if governance were plural and reversible (p ≈ 0.83; avoidability: minimal).

2022 elections proceed on an uneven field (media bias, state-resource misuse) even as they remain competitive—avoidable if campaign–state separation were enforced and opposition coordination improved (p ≈ 0.87; avoidability: low).

Now: opposition holds important municipalities, courts and EU conditionality still bite, and elections continue; avoidability is reduced but real, with p(dominant-party rule) ≈ 0.82–0.88, not converging to 1 so long as external legal/fiscal levers and municipal bases persist.

In sum: Egypt 2–5% vs. Hungary 12–18% → A Hungarian democratic shift is about 2.4× to 9× more likely.

In a tragedy, the characters hurtle toward mutual destruction in a process that feels gradually more inevitable in every scene. In a tyranny, societies feel the same: after each battle, each assassination, each deployment of the military in the cities, after each new piece of freedom-curtailing legislation people feel that fewer options remain. They feel that the escalation is somehow “logical”. In political systems which pose as tyrannies — which use some external kitsch signaling of autocratic rule, but which don’t have any real dictatorial legitimacy or power — each step is reversible with far more ease than those posing up there might want you to think.

Modern wannabe autocrats in the West mess with your head. It’s a process more of gaslighting than of real escalation. Changing the language, changing the visuals, changing the way social media platforms work change your perception of reality. As a human being, an individual, a Tocquevillian participant in society, you are not supposed to be enduring such changes like a child looking for the nearest source of creature comfort and being content being fed bedtime stories. It is your personal and social responsibility to pay attention to what actual reality is. To seek out information and opinions, to double check facts, to discuss the past, the present, and the future with your friends (and enemies); to keep discussing your options.

Look at the establishment of the real dictatorships of yore and you will see, ultimately, past societies that, somehow, step by step, allowed that to happen, allowed that to be done to them. Societies that were first made to believe there was nothing that could have been done, until at some point there was really no way to turn back anymore. Every tyranny is a tragedy. Up to the very last moment there are always way more options than you think: to not flee, to not kill the enemy, to not drink the poison. You don’t have to do it. No one can make you do it.

I love America and choose to live here today because this is a society that tends to know better: where the sovereignty of hundreds of millions of individuals builds into the sovereignty of a nation. Pretty hard to subject so many individualists to oppressive, autocratic rule. Many, many people would first need to give up their right to happiness, to truth and information, to open deliberation and a free media, and the idea that the people in this country were all created equal for that to happen.

This was a pleasure to read. I appreciate the intersection of literature/art and politics in a way that feels enlightening on both.

Lovely and complex and surprising, Anna. So glad you’re doing this & can’t wait to read more.