America, A Love Story

Ragtime, and the romance of the work in progress. A revisitation.

Those of us who love reading history have long noticed that all decades are not made equal. In some ten-year periods, like Heraclitus’s proverbial river, existence flows on in relative uneventfulness. Fields are sown. Babies are born. Lovers woo. Haters hate. The town erects a new bell-tower… In those sleepy decades, great men don’t desire continents and find the courage to take them. Great beauties don’t cheat and cause epic wars and very long poems. Great questions don’t launch heretics onto the cross or the Inquisition’s pyres. And great inventions don’t rattle the markets, making some people instantly poor, and some others very rich. In lackluster decades, people don’t have to find out, for better or worse, what they are made of – they can if they want to, sure, but it’s not inevitable.

Then there are those decades when everything happens. When everything is revealed. Who we are and what we can do. Our sins, our self-deceptions, our goodness. The fluxes of life, after a long time of bubbling ahead in parallel, suddenly converge, reach their maximum pressure point together, and erupt into what in retrospect seems like the obvious outcome. The future.

Few decades were as interesting – in the cheating, conquering, inventing, future-making sense – as the years 1905-1915 in America. When a few weeks ago I had the good luck of hosting an Interintellect salon of EL Doctorow’s novel Ragtime, a favorite reading of my teens, I got sucked back into that chaotic, creative time – a world in the making – that America entering the 20th century was.

The first time I read Ragtime, sprawled on the carpet of my childhood room, I had never been to America, let alone New York where most of this story takes place. I had enjoyed another one of Doctorow’s books, World’s Fair, the story of the author’s own youthful shenanigans among his relatives and other Jewish immigrants in the ‘30s, and so when I opened Ragtime I expected the same cautious, adult nostalgia. Instead, I was ambushed by something very different; an urgent, personal, intellectually exhilarating call – a nationwide provocation!

As its title promises, Ragtime is a ramshackle sideshow, a vaudeville magician’s trick, an often indecent conjuring of the elemental forces of mixing, inventing, exploding, and building, as it blasts through the first decade of modern America when this great country was busy doing just that. Electrifying America — oh, yes. It is no wonder even the less good film adaptation was such a success, and the well-made musical continues to sell out on Broadway to this day.

Spanning out – progressively bicoastally – in beautiful, concise, and inventive prose – a text as intricate and fractal as the lace of Evelyn Nesbitt’s contour when the Jewish artist draws her – Ragtime now made me pause several times just to stare at delicious sentences, photograph sections, go back and reread entire paragraphs. After finishing the novel, I re-read it once again. You know it is good writing when it makes you as insatiable as the era it describes.

Contemporary critics were baffled by what’s best about Ragtime: the book’s unique, rhythmic blending of fact and fiction. Being a tour of that tumultuous decade, we are invited to follow a variety of different plot lines (although not so much to choose our own adventure). Some real people from the crème de la crème of American society pop up and behave as they did in 1906. Admiral Peary or Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish cross our screens and do just what is expected of them. Then there are Doctorow’s entirely fictional creations, archetypes of the time. So much so, many don’t even have names: notably, we are guided through much of the story by the watchful eyes of a character named “the little boy”. (Who is he? Every little boy in America? Every little boy anywhere?) But most of the figures that populate Ragtime are hybrids of these two extremes: personae rooted in and then uprooted from history. The tension here is not just narrative and linguistic, but also epistemic. Is what I am reading true? And does it matter?

In the 1900s, we are at the Dawn of Celebrity: the cities, the newspapers, the dancehalls, the wireless are abuzz. So who could be more elemental, more archetypal in this era than the famous people and what we imagine they’re up to? The book’s fictitious and non-fictitious, just like ragtime tunes, seek to both revolt and entertain. No one in Tocqueville’s America can be content with their lot. It is unimaginable to imagine a satisfied American. The late-Victorian Father goes on expeditions of boredom; the tropics and the poles beckon him vacantly. The justly indignant, self-made Black pianist demands to drive the same Model T as the crowd favorite Jewish immigrant Houdini. They seek out challenges and let challenges find them. The narration jumps from one rebellion to another often within a paragraph even when the characters don’t actually bump into each other – although they often do. Houdini’s Model T literally crashes into Father’s suburban fences!

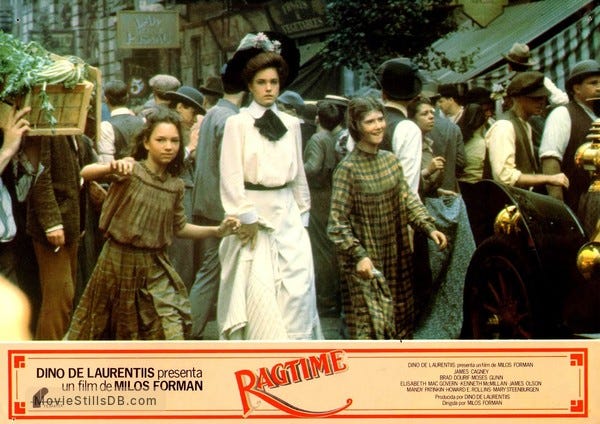

No one’s life story is solitary here, no one remains untouched. This is a time when Stanford White builds seaside mansions fit for entertaining a thousand people. When harbors are extended because the ships keep coming and coming in. A time when mass products are just never enough, and industrialists must rethink manufacturing structurally. The theaters are full, the summer frocks are wet, and the pages of Ragtime emulate, in their density, the undulating multitudes of this era. We are warned early on that the the crashes and the crushes – of cars, of people into each other, of the waves of the sea – are a danger to the old. Something new is being born here, and with it a nation is afoot: dancing, killing, kissing, fleeing. So many new people – new kinds or new-coming – and the chips they’re playing just have not yet fallen. Anything can happen. And it does.

Within this cacophony, like in a great symphony, more intimate motifs also start playing. We zoom in closer on houses, on faces. On sleepless nights. On misunderstandings that cannot in the current language be cleared up. On revolutions that break out in defense of dignity. In Manhattan’s stinking tenements the people of the shtetls live in shoeless misery. Young men in affluent suburbs roam aimlessly in boaters and belle époque ennui. They dream of a sexuality not yet invented. On the beaches, big white hotels packed with nouveau riche immigrants of broken English compete who can hang up more US flags on their champagne-ed verandahs. The specters of Europe, of Egypt – the Origin – loom vaguely as an old dream to plunder.

Frustration, discontent, a running from decay can generate new worlds. In Ragtime, for a long time, nobody is happy. As a result, everybody is innovating. Younger Brother moves on from Fourth of July fireworks to developing military weapons. The Black couple decides to live as equals in society with such firmness that their environment considers acquiescing. Tateh, the Jew, looks down at his hungry child, and decides maybe it’s time to try this capitalism thing after all. To try and find himself and his family a useful place in all this swirl — there must, there must be a place for them too. For anyone. And at an important moment, the Irish maid sits down and lights a cigarette for herself in the living room.

The Old World now is just that, a source. A place where time has stopped — and so America is taking over. I meditate on how, whilst the memory of Ragtime having been a great read had stayed with me since my teens, the only scene I remembered vividly, verbatim, was when Freud and his disciples visit New York City. In his signature syntactic and cinematic playfulness, Doctorow shows us the aging Viennese and his pipe in a taxi as he is driven around a Manhattan he loathes: the noise, the crowds… The advertising! Freud cannot wait to make it back to his cozy study in Austria. But alas, it is too late, warns the author. America has already taken what it wanted from Freud; the doctor can leave as fast as he pleases, he has already changed private life in America.

Thus the coils of this narrative loop into one another on collision courses like in one of Younger Brother’s explosives. Paths are not crossed here, rather stuffed to the brim full of people; a myriad of dramas in a myriad of heads. I greatly love books like this; they feel just like real life. Where everyone must stay true to oneself and yet everyone can have a deep effect on whomever they encounter. The heart of the human social mystery.

And so just like at 15, I was again thrilled by this story, the language, the morals, the characters. By the humility of an excellent author of personalities – omniscient, to some degree, yes, but he knows well every human is a black box. Even when we hear their internal reasoning, the behavior is surprising to us – and to them. Even when we know their external determinism — their circumstances, norms, and stressors — we might soon observe them triumphing against the tide.

In a way that is very hard to do, Ragtime is a great book about men and women. Because of all the revolts that bring about the 20th century in America, it is the women’s that is the greatest.

The women of Ragtime emerge from the primordial mass of archetypes too, the Excel sheet of storybook canon, and yet they break free of these archetypes, they transcend them. There is the Mother, the Revolutionary, and the Whore. Of course: the American triumfeminate. While the men are busy taking hostages, inventing the assembly line, playing music, and sometimes shooting each other, the women will cross class, geographical, and racial boundaries and alchemize the social future of America.

The Revolutionary is of course Emma Goldman, the workers’ agitator — a woman who is both a total novelty at the time and already a gigantic cliché. In the decade when being a Marxist actually seemed to make sense (your kid had to work in a factory 15 hours a day and probably lost a leg or two when he got a bit drowsy toward the evening), her speeches helped America’s quasi-proletariat keep their wits about them. It is an ironic twist of history that the rights and prosperity Goldman so encouraged her acolytes to aim for were — and are — a product instead of capitalism, as Tateh, in his darkest and most self-honest hour, comes to admit to himself and thus change his life.

Goldman steps out of her archetype like a used petticoat when we learn she is in fact a gentle socialite, a polyamorous nurse, a kind of hippy. It is not through her vehemence and notoriety but her tenderness and connections that Goldman ends up influencing the other two heroines, directly or indirectly; her ideas of female intellectual freedom, economic independence, sexual expression, and contraceptive planning enlighten and liberate an entire generation.

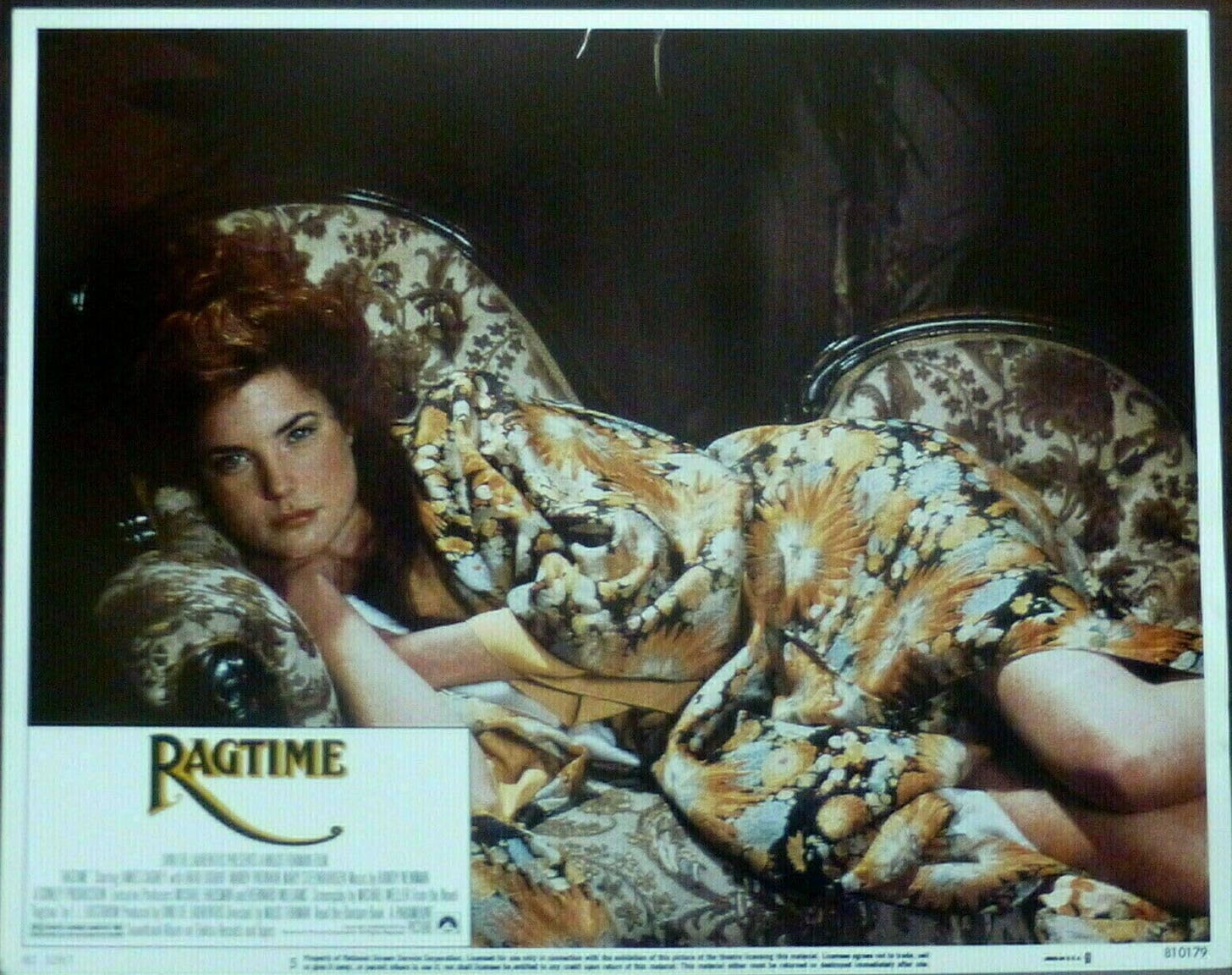

The Whore is the in/famous Evelyn Nesbitt, the first American starlet. The Celeb. The girlfriend of famous men. She is photographed, painted, whipped by a pervert, and in general paid good money for (although never what she is worth, Emma Goldman warns her, just what the men find not too much to give!). The real Evelyn Nesbitt, the beautiful, paintable choirgirl, lived into her 80s, and indeed was a far more proactive and creative person than her demimonde beginnings would suggest. Her inventiveness is evoked in Ragtime: after her husband and tormentor Harry Kendall Thaw (a railroad heir) shoots her old lover and mentor Stanford White (the architect) and she nails the planned courthouse testimony so he can be judged insane, the young courtesan has some kind of epiphany and decides that if she can’t help herself at least she should help another girl. Thus begins her unspoken friendship with Tateh, the artist of the tenements, in whose daughter Evelyn finds her altruistic cause. This being America, the moralist Tateh, who previously banished his own wife for “prostitution” after the starving woman was assaulted by her employer, now has to accept the charity of the country’s most famous harlot. Just one of the things he has to learn to live with... And from her end, Evelyn’s donations help the broken man develop what would in a few years become the motion picture industry of California. But we’ll get there soon.

The greatest rebel in Ragtime is of course Mother. This nameless everywoman, this respectable housewife, is the first to learn, in the dark hypocrisies of her middle-class marriage bed, that some things are just no longer working in America. She is the one who sees through it — she doesn’t even immediately know what. She changes the wallpaper. She talks back at her husband. She literally invites change, in the form of a Black baby, into her home. She scoffs at self-delusion. She insists, eventually breaking down everybody’s resistance, on doing what is right. She starts out with the most clearly outlined cage; the wide hat blocking her view, the front porch’s delineation, the corset. And she liberates herself and her family, in a collaboration between her character and our history, until all 19th century pretenses are gone, and it is just love, and truth, and open spaces that remain.

Ragtime is a romance of innovation, and through the mythical figure of Mother we come to learn the greatest innovation of America is love. We’re deep in the Tocquevillian territory of free association, and Mother associates freely alright. The love for the different, the strange, the new, the other, the lovable ripple through this text with acceptance and certitude. Be that the Black child Mother shelters in her home and thus catalyses the destinies of a whole group of people. Or the couple she will end up forming with the now wealthy filmmaker Tateh, the epitome of the entrepreneurial Jew, a parvenu. When in the end Mother drives her Model T away into the Western sunset – California-bound, no less – she has become the steward of a hopeful and mixed family ready for all that will be new in the 20th century.

All innovation is first and foremost self-reinvention, and so Ragtime is also a story of the stories we tell ourselves. We start with Houdini’s shabby roadside wizardry, and the freak show the children sneak away to see in Atlantic City – and we wind up in Hollywood, in a new industry tasked with helping an eager, growing new culture define and understand itself through spectacle and awe, a celebration of community and shared experience.

JP Morgan might sail to the pyramids and bring home ancient treasures for his marble library. But while the rich are busy thus entombing themselves in the past, the masses have invented a new religion. It is loud, for sure, has questionable manners, speaks in a strange accent, is obsessed with money, always seeks to make new friends, and it is very, very American.

***

There is a book on the bookshelf, for years and years, and one’s hand somehow never stops on it, it is never re-opened. Then something shifts – in one of the many Doctorowesque plot lines of real life – and you think: I should re-read Ragtime. Now. It has to be now.

I often wonder how this happens. Do we have a “book instinct”? A kind of bibliomancy where the choice of the book is already the prophecy? I’d never thought of revisiting Mother, Coalhouse Walker Jr., Emma, Henry Ford, and the little boy until early 2026 when it was suddenly the obvious pick somehow. I believe it is because this current period too, like the 1905-1915 decade, is a time when all events accelerate. America is changing. The world is changing. People are often confused. People are often wrong. Everybody’s looking for answers to questions we haven’t even yet come up with. There is a new humility brewing, perhaps. One where one might say: I don’t know, but I will try.

2025 was a particularly hard and disorienting year for many people I know – thoughtful and competent folks, not normally prone to being so unsure. I took it seriously. It was in the air everywhere. I felt it too – the motivation for innovation, but also a fear of decay. Today I think it was because 2025 was somehow the last year of the old times. The clocks in America are resetting. A new culture is forming, innovating, breaking through. A new energy. A new love. New Americans, looking for stories through which to reflect on themselves. Nobody knows anything, but we will try.

And so Ragtime feels urgent again, overwhelming and clarifying. A book about abundant futures and free association. For the decades when everything happens.